The Department for Transport, the Military Aviation Authority and British Airline Pilots’ Association commissioned a study into the effects of a mid-air collision between small remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS, commonly known as a drones) and manned aircraft.

The study was conducted by QinetiQ and Natural Impacts using laboratory collision testing and computer modelling. This report was authored jointly by the commissioning stakeholders in order to summarise the findings of this work performed by QinetiQ, and give consideration to how the results will be used.

This study aimed to find the lowest speed at collision where critical damage could occur to aircraft components. Critical damage was defined in this study to mean major structural damage of the aircraft component or penetration of drone through the windscreen into the cockpit.

The study has indicated that:

- Non-birdstrike certified helicopter windscreens have very limited resilience to the impact of a drone, well below normal cruise speeds.

- The non-birdstrike certified helicopter windscreen results can also be applied to general aviation aeroplanes which also do not have a birdstrike certification requirement.

- Although the birdstrike certified windscreens tested had greater resistance than non-birdstrike certified, they could still be critically damaged at normal cruise speeds.

- Helicopter tail rotors are also very vulnerable to the impact of a drone, with modelling showing blade failures from impacts with the smaller drone components tested.

- Airliner windscreens are much more resistant, however, the study showed that there is a risk of critical windscreen damage under certain impact conditions:

─ It was found that critical damage did not occur at high, but realistic impact speeds, with the 1.2 kg class drone components.

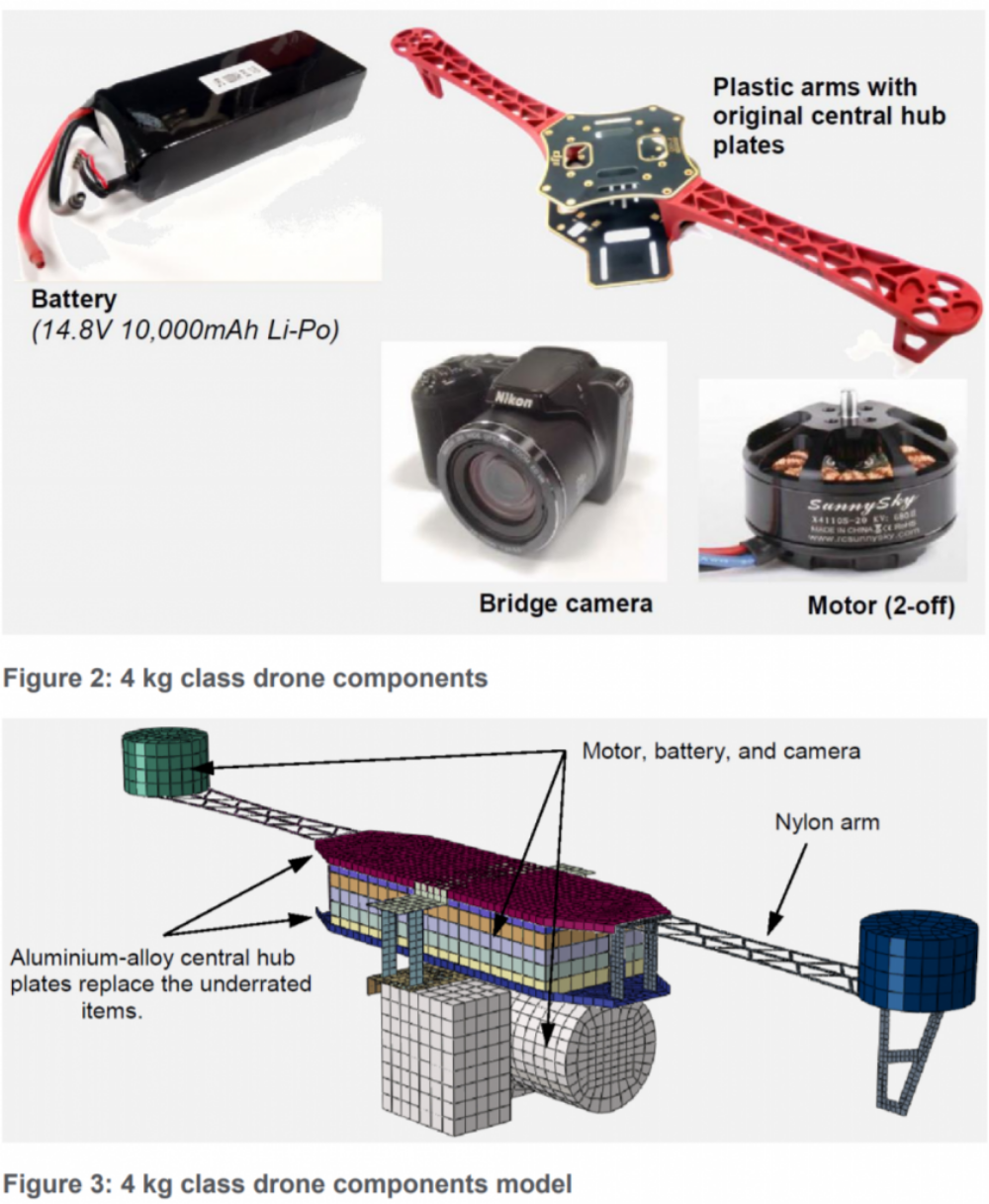

─ However, critical damage did occur to the airliner windscreens at high, but realistic, impact speeds, with the 4 kg class drone components used in this study.

- The construction of the drone plays a significant role in the impact of a collision. Notably, the 400 g class drone components, which included exposed metal motors, caused critical failure of the helicopter windscreens at lower speeds than the 1.2 kg class drone components, which had plastic covering over their motors. This is believed to have absorbed some of the shock of the collision, reducing the impact.

- The testing and modelling showed that the drone components used can cause significantly more damage than birds of equivalent masses at speeds lower than required to meet bird strike certification standards.

The study resulted in an increase in knowledge regarding the severity of a mid-air collision between a manned aircraft and a small drone. It should be noted that to understand the risk fully, work should also be done to estimate the likelihood of a collision.

Recommendations were made on further work and possible mitigations and, alongside other work evaluating the likelihood of a collision, will be used to inform future rules and regulations on the use of drones.

The 18-page study can be accessed here.

Source: Report

All people individuals working with and flying RPAS’s / UAV’s need to read this report or at least the summary. This includes those individuals who are flying under as model aircraft with reduced restrictions and registration requirements.

Bottom line for the Pilots in Command of UAV’s – You are putting people at risk when you fly within the designated airspace of conventional aircraft.

Niel

If a UAV were hit by an airliner and just the slightest bit of damage is inflicted to a windscreen or radome, the airline would incur thousands of dollars in component replacement.