At Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, two miles from the cow pasture where the Wright Brothers learned to fly the first airplanes, military researchers are at work on another revolution in the air: shrinking unmanned drones, the kind that fire missiles into Pakistan and spy on insurgents in Afghanistan, to the size of insects and birds.

The base’s indoor flight lab is called the “microaviary,” and for good reason. The drones in development here are designed to replicate the flight mechanics of moths, hawks and other inhabitants of the natural world. “We’re looking at how you hide in plain sight,” said Greg Parker, an aerospace engineer, as he held up a prototype of a mechanical hawk that in the future might carry out espionage or kill.

Half a world away in Afghanistan, Marines marvel at one of the new blimplike spy balloons that float from a tether 15,000 feet above one of the bloodiest outposts of the war, Sangin in Helmand Province. The balloon, called an aerostat, can transmit live video — from as far as 20 miles away — of insurgents planting homemade bombs. “It’s been a game-changer for me,” Capt. Nickoli Johnson said in Sangin this spring. “I want a bunch more put in.”

From blimps to bugs, an explosion in aerial drones is transforming the way America fights and thinks about its wars. Predator drones, the Cessna-sized workhorses that have dominated unmanned flight since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, are by now a brand name, known and feared around the world. But far less widely known are the sheer size, variety and audaciousness of a rapidly expanding drone universe, along with the dilemmas that come with it.

The Pentagon now has some 7,000 aerial drones, compared with fewer than 50 a decade ago. Within the next decade the Air Force anticipates a decrease in manned aircraft but expects its number of “multirole” aerial drones like the Reaper — the ones that spy as well as strike — to nearly quadruple, to 536. Already the Air Force is training more remote pilots, 350 this year alone, than fighter and bomber pilots combined.

“It’s a growth market,” said Ashton B. Carter, the Pentagon’s chief weapons buyer. The Pentagon has asked Congress for nearly $5 billion for drones next year, and by 2030 envisions ever more stuff of science fiction: “spy flies” equipped with sensors and microcameras to detect enemies, nuclear weapons or victims in rubble. Peter W. Singer, a scholar at the Brookings Institution and the author of “Wired for War,” a book about military robotics, calls them “bugs with bugs.”

In recent months drones have been more crucial than ever in fighting wars and terrorism. The Central Intelligence Agency spied on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan by video transmitted from a new bat-winged stealth drone, the RQ-170 Sentinel, otherwise known as the “Beast of Kandahar,” named after it was first spotted on a runway in Afghanistan. One of Pakistan’s most wanted militants, Ilyas Kashmiri, was reported dead this month in a C.I.A. drone strike, part of an aggressive drone campaign that administration officials say has helped paralyze Al Qaeda in the region — and has become a possible rationale for an accelerated withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan. More than 1,900 insurgents in Pakistan’s tribal areas have been killed by American drones since 2006, according to the Web site www.longwarjournal.com.

In April the United States began using armed Predator drones against Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi’s forces in Libya. Last month a C.I.A.-armed Predator aimed a missile at Anwar al-Awlaki, the radical American-born cleric believed to be hiding in Yemen. The Predator missed, but American drones continue to patrol Yemen’s skies.

Large or small, drones raise questions about the growing disconnect between the American public and its wars. Military ethicists concede that drones can turn war into a video game, inflict civilian casualties and, with no Americans directly at risk, more easily draw the United States into conflicts. Drones have also created a crisis of information for analysts on the end of a daily video deluge. Not least, the Federal Aviation Administration has qualms about expanding their test flights at home, as the Pentagon would like. Last summer, fighter jets were almost scrambled after a rogue Fire Scout drone, the size of a small helicopter, wandered into Washington’s restricted airspace.

Within the military, no one disputes that drones save American lives. Many see them as advanced versions of “stand-off weapons systems,” like tanks or bombs dropped from aircraft, that the United States has used for decades. “There’s a kind of nostalgia for the way wars used to be,” said Deane-Peter Baker, an ethics professor at the United States Naval Academy, referring to noble notions of knight-on-knight conflict. Drones are part of a post-heroic age, he said, and in his view it is not always a problem if they lower the threshold for war. “It is a bad thing if we didn’t have a just cause in the first place,” Mr. Baker said. “But if we did have a just cause, we should celebrate anything that allows us to pursue that just cause.”

To Mr. Singer of Brookings, the debate over drones is like debating the merits of computers in 1979: They are here to stay, and the boom has barely begun. “We are at the Wright Brothers Flier stage of this,” he said.

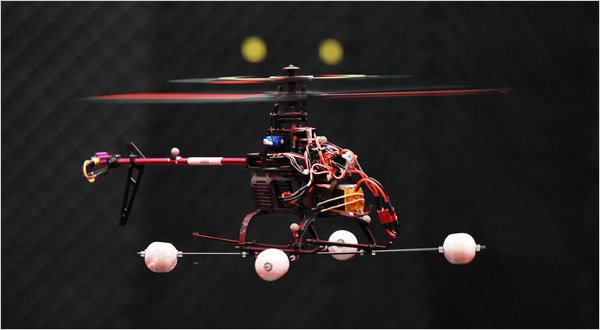

A tiny helicopter is buzzing menacingly as it prepares to lift off in the Wright-Patterson aviary, a warehouse-like room lined with 60 motion-capture cameras to track the little drone’s every move. The helicopter, a footlong hobbyists’ model, has been programmed by a computer to fly itself. Soon it is up in the air making purposeful figure eights.

“What it’s doing out here is nothing special,” said Dr. Parker, the aerospace engineer. The researchers are using the helicopter to test technology that would make it possible for a computer to fly, say, a drone that looks like a dragonfly. “To have a computer do it 100 percent of the time, and to do it with winds, and to do it when it doesn’t really know where the vehicle is, those are the kinds of technologies that we’re trying to develop,” Dr. Parker said.

The push right now is developing “flapping wing” technology, or recreating the physics of natural flight, but with a focus on insects rather than birds. Birds have complex muscles that move their wings, making it difficult to copy their aerodynamics. Designing insects is hard, too, but their wing motions are simpler. “It’s a lot easier problem,” Dr. Parker said.

In February, researchers unveiled a hummingbird drone, built by the firm AeroVironment for the secretive Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which can fly at 11 miles per hour and perch on a windowsill. But it is still a prototype. One of the smallest drones in use on the battlefield is the three-foot-long Raven, which troops in Afghanistan toss by hand like a model airplane to peer over the next hill.

There are some 4,800 Ravens in operation in the Army, although plenty get lost. One American service member in Germany recalled how five soldiers and officers spent six hours tramping through a dark Bavarian forest — and then sent a helicopter — on a fruitless search for a Raven that failed to return home from a training exercise. The next month a Raven went AWOL again, this time because of a programming error that sent it south. “The initial call I got was that the Raven was going to Africa,” said the service member, who asked for anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss drone glitches.

In the midsize range: The Predator, the larger Reaper and the smaller Shadow, all flown by remote pilots using joysticks and computer screens, many from military bases in the United States. A Navy entry is the X-47B, a prototype designed to take off and land from aircraft carriers automatically and, when commanded, drop bombs. The X-47B had a maiden 29-minute flight over land in February. A larger drone is the Global Hawk, which is used for keeping an eye on North Korea’s nuclear weapons activities. In March, the Pentagon sent a Global Hawk over the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan to assess the damage.

The future world of drones is here inside the Air Force headquarters at Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., where hundreds of flat-screen TVs hang from industrial metal skeletons in a cavernous room, a scene vaguely reminiscent of a rave club. In fact, this is one of the most sensitive installations for processing, exploiting and disseminating a tsunami of information from a global network of flying sensors.

The numbers are overwhelming: Since the Sept. 11 attacks, the hours the Air Force devotes to flying missions for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance have gone up 3,100 percent, most of that from increased operations of drones. Every day, the Air Force must process almost 1,500 hours of full-motion video and another 1,500 still images, much of it from Predators and Reapers on around-the-clock combat air patrols.

The pressures on humans will only increase as the military moves from the limited “soda straw” views of today’s sensors to new “Gorgon Stare” technology that can capture live video of an entire city — but that requires 2,000 analysts to process the data feeds from a single drone, compared with 19 analysts per drone today.

At Wright-Patterson, Major Michael L. Anderson, a doctoral student at the base’s advanced navigation technology center, is focused on another part of the future: building wings for a drone that might replicate the flight of the hawk moth, known for its hovering skills. “It’s impressive what they can do,” Major Anderson said, “compared to what our clumsy aircraft can do.”

Source: New York Times