The US Army just handed out a half-dozen contracts to firms to find faces from above, track targets, and even spot “adversarial intent.”

“If this works out, we’ll have the ability to track people persistently across wide areas,” says Tim Faltemier, the lead biometrics researcher at Progeny Systems Corporation, which recently won one of the Army contracts. “A guy can go under a bridge or inside a house. But when he comes out, we’ll know it was the same guy that went in.”

Progeny just started work on their drone-mounted, “Long Range, Non-cooperative, Biometric Tagging, Tracking and Location” system. The company is one several firms that has developed algorithms for the military that use two-dimensional images to construct a 3D model of a face. It’s not an easy trick to pull off — even with the proper lighting, and even with a willing subject. Building a model of someone on the run is harder. Constructing a model using the bobbing, weaving, flying, relatively low-resolution cameras on small unmanned aerial vehicles is tougher still.

But it could be of enormous military value. “This overcomes a basic limitation in current TTL operations where … objects of interest only appea[r] periodically from sheltered positions or crowds,” the Army noted in its announcement of the project.

That’s what Progeny claims it can do: take an existing unmanned aircraft, like the hand-held Raven, and turn it into a TTL machine. “Any pose, any expression, any lighting,” Faltemier says. Progeny needs an image with just 50 pixels between the target’s eyes to build a 3D model of his face. That’s about the same as what it takes to traditionally capture a 2D image. (Naturally, the model gets better and better the more pictures are taken during enrollment.) Once the target is “enrolled” in Progeny’s system, it might only take 15 or 20 pixels to identify him again. A glance or two at a Raven’s camera might conceivably be enough.

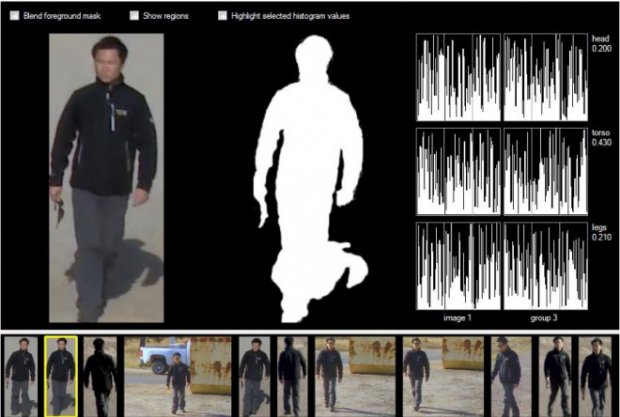

And if the system can’t get a good enough look at a target’s face, Progeny has other ways of IDing its prey. The key, developed under a previous Navy contract, is a kind of digital stereotyping. Using a series of so-called “soft biometrics” — everything from age to gender to “ethnicity” to “skin color” to height and weight — the system can keep track of targets “at ranges that are impossible to do with facial recognition,” Faltemier says. Like 750 feet away or more.

But if Progeny can get close enough, Faltemier says his technology can even tell identical twins apart. With backing by the Army, researchers from Notre Dame and Michigan State Universities collected images of faces at a “Twins Days” festival. Progeny then zeroed in on the twins’ scars, marks, and tattoos — and were able to spot one from the other. The company says the software can help the military “not only learn the identity of subjects but also their associations in social groups.”

The Pentagon isn’t content to simply watch the enemies it knows it has, however. The Army also wants to identify potentially hostile behavior and intent, in order to uncover clandestine foes.

Charles River Analytics is using its Army cash to build a so-called “Adversary Behavior Acquisition, Collection, Understanding, and Summarization (ABACUS)” tool. The system would integrate data from informants’ tips, UAS footage, and captured phone calls. Then it would apply “a human behavior modeling and simulation engine” that would spit out “intent-based threat assessments of individuals and groups.” In other words: This software could potentially find out which people are most likely to harbor ill will toward the US military or its objectives.

“The enemy goes to great lengths to hide his activities,” explains Modus Operandi, Inc., which won an Army contract to assemble “probabilistic algorithms th[at] determine the likelihood of adversarial intent.” The company calls its system “Clear Heart.” As in, the contents of your heart are now open for the Pentagon to see. It may be the most unnerving detail in this whole unnerving story.

Source: Wired Danger Room