In the second week of December, an unmanned aircraft flew over the Maoist-hit areas of Dantewada district in Chhattisgarh, picking up images of village dwellings and human movement.

At the National Technical Research Organisation (NTRO) control room the information was treated as a major breakthrough since the drones deployed in the area had so far failed to provide sufficient intelligence inputs. The state and paramilitary forces were also convinced that the images were of a Naxal camp. An operation was immediately planned. Surprise and speed were to be the key elements.

The operation was to be similar in nature to the ones successfully undertaken by the US-led allied forces in Afghanistan and Pakistan. A surrendered Maoist was also quizzed to clear the doubts about the target location.

Armed with the visuals provided by the Heron drone, a team of two units, comprising paramilitary was dispatched on foot to encircle and sanitize Teriwal village in Dantewada. Another 125 personnel were to be air dropped at the assembly area which was some kilometres away from the presumed Naxal camp at Teriwal, as was indicated by the footage relayed by the UAV.

But on December 19, an air force MI-17 helicopter with armed personnel on board came under fire while it was carrying out its 10th sortie. Two shots hit the rotor of the helicopter. The men had a lucky escape.

The sudden attack on the chopper caught the forces off guard. The UAV images clearly did not provide any indication of Maoist movement in the area, which was chosen to drop security personnel and was far away from the presumed rebel camp. The drone image virtually led the forces into a trap. The suspicion about the images grew when it was discovered that the presumed Naxal camp was a nondescript village.

“Several huts and human movement were captured by the UAV cameras in Teriwal village. So it was presumed that it could be a Naxal camp,” a government source said. Chhattisgarh inspector general of police (Bastar range) T. J. Longkumer said: “Given all the factors, the operation was successful. I will not be able to comment on the UAV images. But it is very difficult to differentiate between a Naxal hideout and a normal settlement.”

On the effective use of the UAVs in the war against Naxals, Longkumer stated: “We have just started getting footage from the UAV. It’s too early to talk about the drones’ success in getting live information.” Officially, it was shown as a successful operation as seven obsolete muzzle- loading rifles, generally used in hunting, were seized and made to look like Naxal weapons. But the inside story was to the contrary.

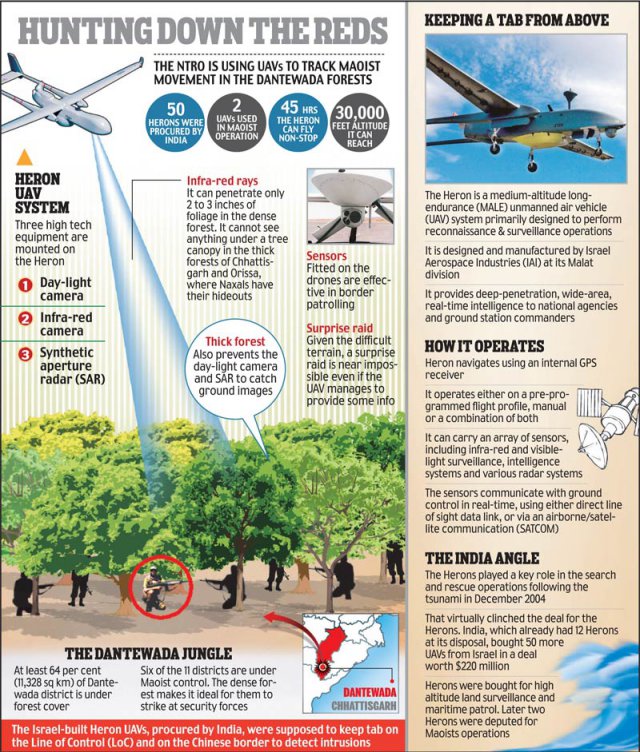

This fiasco has raised questions on the drone-backed operations in Maoist areas. The UAVs were procured by the Indian armed forces for high altitude land surveillance and maritime patrol missions. But they are proving unsuccessful in tracking down Maoists since the infra- red rays emitted by the synthetic aperture radar operate with perfection in a clear landscape, but are unable to penetrate foliage in the jungle, an officer aware of the development, said.

“Images provided by drones are not actionable since it cannot penetrate foliage and many a times we have dumped these images and videos since there were nothing that could have helped us. In the Chhattisgarh operation, it gave us pictures of huts and people, but who will judge if they were really Maoists?” a senior officer said.

Another officer involved in the Naxal operation in Chhattisgarh was even more critical. “Even if the UAV spots human beings, the question is what to do with that information? You just cannot shoot at anything that the drone spots in the jungle. This is our own country and we are not an American in Afghanistan,” he said.

The tough terrain in the jungle also makes it difficult for the forces to cover the un-motorable distance on foot. The speed of movement in the jungle, depending on the terrain, could be as slow as a couple of kilometres an hour. By the time the forces reach the spot, the Naxals could be somewhere else, the officer added.

Source: India Today