Increased use of unmanned aircraft is driving demand for smaller precision-attack weapons.

Strike weapons is the only segment of the world missile-systems market expected to see significant increases in value and production through 2016, with the lightweight missile sub-segment projected to experience rapid growth.

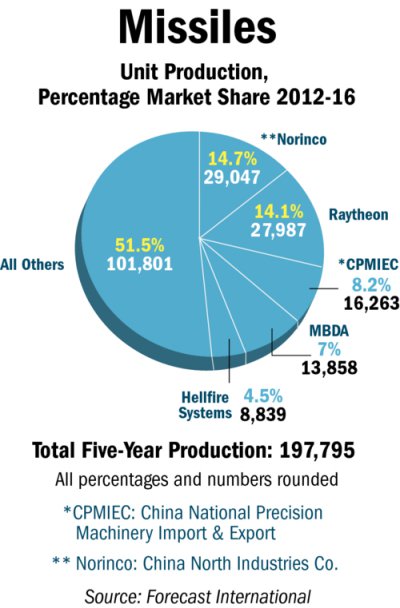

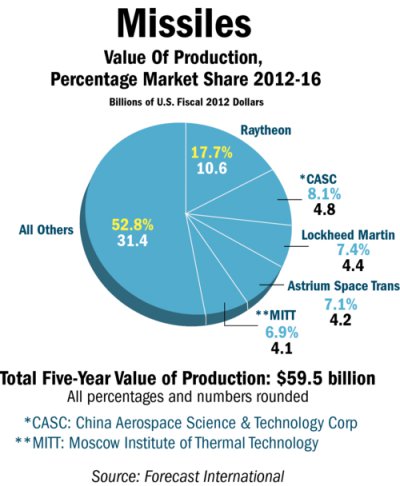

The world missile market is forecast to see a slight increase in value from a low of $11.18 billion in 2012 to a high of $11.81 billion in 2016, but production is expected to drop, reflecting the high price of some systems. Annual purchases of lightweight missiles is currently low, but will reach $60 million in 2016.

Although examined since U.S. involvement in Somalia in the early 1990s, the lightweight precision-attack missile concept did not catch on until the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan changed the focus of combat from conventional warfare to counterinsurgency.

Although examined since U.S. involvement in Somalia in the early 1990s, the lightweight precision-attack missile concept did not catch on until the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan changed the focus of combat from conventional warfare to counterinsurgency.

The battle against insurgents soon saw the U.S. expanding its use of unmanned aircraft to monitor thousands of square miles. Although acquired to gather intelligence, some of these UAS had the ability to engage ground targets, and field commanders quickly exploited this capability.

The number of air strikes by unmanned aircraft has escalated. Along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, only one took place in 2004-05, three in 2006 and five in 2007. But air strikes in the region increased to 35 in 2008, 53 in 2009 and 117 in 2010, with reports of a similar number expected for 2011-not including those in Libya, Iraq, Yemen and Somalia.

In the beginning, the U.S. armed its unmanned aircraft with available Hellfire missiles. Although these munitions met the Pentagon’s requirements, some critics considered this anti-tank missile to be overkill, as the targets were usually unarmored vehicles, houses or individuals. At more than 100 lb., Hellfire’s weight also limited its deployment to small numbers on larger Predator-class UAS.

New weapons were needed, more closely tailored to a UAS-based air campaign. Lighter missiles would allow UAS to carry more weapons and attack more targets during a single mission, while their smaller warheads would reduce collateral damage.

Among this new generation of lightweight missiles is Raytheon’s Griffin, which is available in two versions: the air-launched “A” model carried by aircraft such as Air Force Special Operations Command’s MC-130W Combat Spear; and the tube-launched “B” model, which can be fired from unmanned aircraft, ground vehicles and helicopters.

Among this new generation of lightweight missiles is Raytheon’s Griffin, which is available in two versions: the air-launched “A” model carried by aircraft such as Air Force Special Operations Command’s MC-130W Combat Spear; and the tube-launched “B” model, which can be fired from unmanned aircraft, ground vehicles and helicopters.

Griffin uses GPS, inertial and laser guidance. A Predator can carry three Griffins for each Hellfire, its small size making it possible to arm a greater variety of UAVs. The U.S. Navy may even place a version on its Littoral Combat Ship, Griffin replacing the Non-Line-of-Sight missile canceled in 2010.

Other U.S.-developed lightweight missiles include the Lockheed Martin Small Smart Weapon (SSW), or Scorpion. This is a rival to the GBU-44 Viper Strike munition, originally developed by Northrop Grumman and now owned by MBDA. The unpowered, 44-lb. Viper Strike is deployed as the Special Operations Precision Guided Munition (SOPGM). The 35-lb. Scorpion has a larger warhead and is adaptable to multiple launch platforms. Reports suggest the Scorpion was hitting targets in Pakistan’s tribal region by March 2010. Its greater accuracy is credited with reducing civilian casualties.

Source: Aviation Week