Unmanned aircraft are currently being tried out in vineyards in the south of France, to check that “grubbing up” of vines is done legally and ecologically.

Wine-growers get as much as 10,000 euros ($13,000; £8,300) per hectare in subsidies for digging up uncompetitive vines – a scheme to prevent new EU “wine lakes” caused by overproduction.

“There has to be 100% control, as it’s a huge amount of money,” says Philippe Loudjani, an agronomist at the Joint Research Centre, the European Commission’s main satellite monitoring hub in Ispra, northern Italy. “The French are testing to see if the UAS need to go up to 10cm resolution – to see what accuracy is required.”

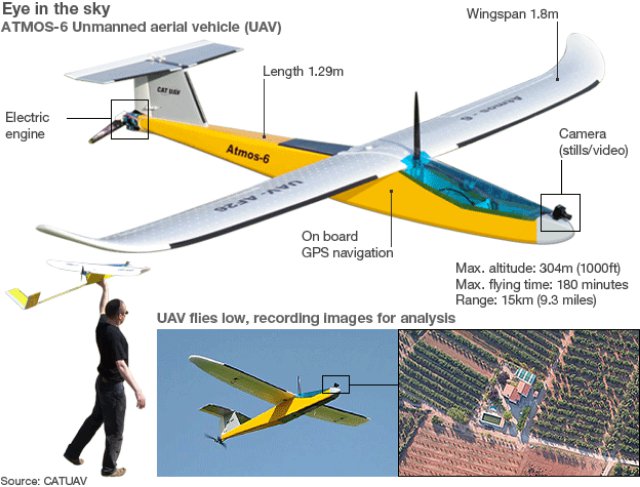

UAS are also being tested in Italy, and are already in use on a small scale in Spain’s Catalonia region, where authorities say their 25 cm and 12.5 cm resolution photos are ideal for inspecting the small landholdings with mixed crops that are typical of the Mediterranean and produce better results than photos taken from manned aircraft. Spanish company CATUAV has been offering a wide range of services since 2003 in the ares of agriculture, viticulture, geology, hydrology and environmental protection.

The EU is hurrying to develop a “strategy for Unmanned Aircraft Systems”, which would see the existing very tough restrictions on the use of civilian UAS in Europe relaxed.

A discussion paper prepared for a European Commission workshop in Brussels this week, envisages their use not only in crop or farm monitoring, but also terrain cartography, goods transport, monitoring of borders, the fight against illegal immigration and drug trafficking, and intervention in natural or industrial disasters.

However, in the short term it’s likely that UAS will only be widely approved for use within line of sight of an operator and at a distance of no more than 500m, which limits their value for agricultural inspection.

Source: BBC