The Pentagon has a big command-and-control problem. Not insubordination among the troops. It’s that unmanned systems for land, air and sea—for which the military spent $6 billion-plus last year—can’t “talk” to one another.

The Pentagon has a big command-and-control problem. Not insubordination among the troops. It’s that unmanned systems for land, air and sea—for which the military spent $6 billion-plus last year—can’t “talk” to one another.

Every UAS contractor builds proprietary control systems, making it impossible to integrate different machines or for the military to tinker with existing systems. “It can only be described as byzantine,” says retired Lieutenant General Dave Deptula, once the Air Force’s First Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance, and thus in charge of UAS that have been deployed to devastating effect in Afghanistan, Iraq and Yemen.

That’s great for UAS builders. The unique software codes and operating features lock the Pentagon into an exclusive and expensive relationship.

Nelson Paez is trying to break that lock. His company, DreamHammer, has spent $5 million building an operating system, Ballista, that can link and control any kind of UAS or robot, armed or unarmed. If the military adopts it, manufacturers like Northrop Grumman and Boeing would have to license Paez’s software so their unmanned systems could be plugged into the military’s.

“We’ve been working with the government for the past three years on this,” says Paez, a tall Californian who, Men in Black-style, sports wraparound sunglasses and a dark suit. “When I first told Defense officials about Ballista, they stood up and said, ‘That’s what we’ve been waiting for for years.’”

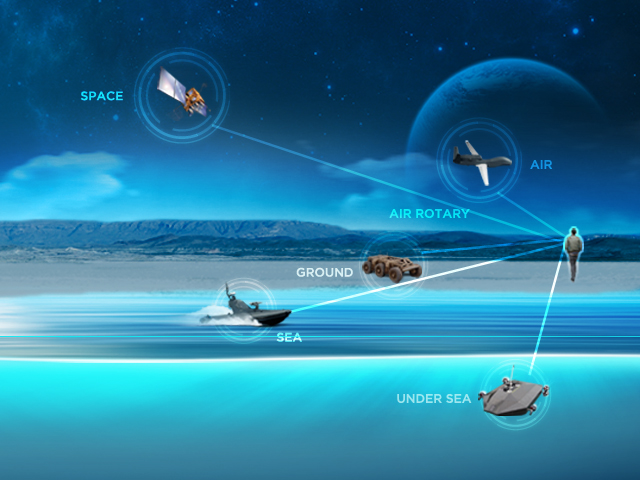

Ballista’s system is so simple it can be run from a tablet. The software interfaces with an unmanned aircraft via an application programming interface, a.k.a. API. Each aircraft’s unique software codes, operational hardware protocols and data transmissions flow into Ballista’s central command system to be translated and displayed in a videogame-like user interface. The system streams thermal imaging information from cameras, geo-locating data and flying controls for surveillance drones—and serves as a trigger for armed ones. UAS that can’t now be networked could then communicate with one another.

Ballista’s system is so simple it can be run from a tablet. The software interfaces with an unmanned aircraft via an application programming interface, a.k.a. API. Each aircraft’s unique software codes, operational hardware protocols and data transmissions flow into Ballista’s central command system to be translated and displayed in a videogame-like user interface. The system streams thermal imaging information from cameras, geo-locating data and flying controls for surveillance drones—and serves as a trigger for armed ones. UAS that can’t now be networked could then communicate with one another.

DreamHammer CTO Chris Diebner compares it with a smartphone OS—on which UAS and features for them can be run like apps. Of course, Ballista is doing something on a much larger scale. It means that it takes fewer people to fly more UAS and that new features can be rolled out without the need to develop and build a new version of a Predator, for example.

Now 38, Paez spent the late 1990s doing IT security work for the Defense Logistics Agency. He cofounded Dream-Hammer in 2000 to provide identity management systems and IT security to companies like Country Financial, Pfizer and Best Buy. Today it’s a 75-person shop out of Santa Monica, Calif., Honolulu and Arlington, Va. doing only government work. It has a current backlog of $23 million in U.S. contracts and netted 15% on revenue of $6.9 million last year.

In 2008, with talk of in-sourcing jobs and military budget cuts, Paez pondered new opportunities. He asked Pentagon contacts about their biggest challenges— and responded with an open architecture for robot operations. Into Ballista went a total $2.5 million of reinvested profits, $1 million from angel investors—and the brainpower of engineers recruited from the likes of Raytheon, Northrop Grumman and General Atomics.

Now in beta, Ballista is being tested by military labs paying $1.5 million to do so. DreamHammer plans to release the product in 2013, along with software development kits so drone contractors can develop “apps” on the Ballista system.

Paez is seeking $20 million in funding for the next phase: commercial applications. Congress ordered the Federal Aviation Administration to allow for private drones in the national airspace by 2015. That puts companies like FedEx and UPS on DreamHammer’s radar.

Images from DreamHammer

Source: Forbes