Lockheed Martin has crafted a reduced-cost plan to “optionally man” its U-2, throwing a new possibility into the mix as Congress weighs whether to shift to an all-Northrop Grumman Global Hawk unmanned aircraft fleet for high-altitude reconnaissance. With an optionally manned U-2, advocates for the so-called Dragon Lady say the venerable aircraft finally can match the endurance offered by the RQ-4B Global Hawk. Convincing lawmakers and the Pentagon likely will be an uphill battle, though.

The Office of the Secretary of Defense finally opted after more than a decade of waffling to commit to a U-2 retirement path in its fiscal 2015 budget request, carving a path for an all-Global Hawk fleet. But U-2 advocates are continuing to argue that its attributes—including a 5,000-lb. payload—are superior to those of the Global Hawk, a high-flying unmanned aircraft capable of lofting 3,000 lb. of sensors. The U-2 operates at 70,000 ft. while the Global Hawk is limited to 60,000 ft., reducing its slant angle—or sensor range—for targets. It also lacks defensive systems that the U-2 carries.

Advocates of the two programs have been in a tit-for-tat funding dispute for nearly 15 years, each annually attempting to raid the other’s budget and gain support from combatant commanders. The Pentagon’s final ruling this year calls for a $1.8 billion upgrade for the Global Hawk to achieve near-parity with the U-2, with the main focus to improve the reliability and sensor performance of the unmanned aircraft. Based on an April report to Congress, the Air Force is spending $9.1 billion on the Global Hawk program to develop and buy 45 aircraft, including seven baseline Block 10s, six Block 20s (some outfitted with the Battlefield Airborne Communications Node relay), 21 Block 30s capable of imagery and signals intelligence and 11 Block 40s operating the radar payload.

Originally the product of a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency experiment to design an inexpensive unmanned aerial system, Global Hawk was thrust into operation to support a spike in reconnaissance requirements after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It has been supporting operations in the Middle East and Asia since then, gaining operational experience it likely never would have received had the U.S. not conducted operations in Afghanistan. And, eventually, Global Hawk earned a place as a potential replacement for the U-2.

Its strongest edge over the U-2 remains its endurance; the Global Hawk can stay aloft for 24 hr. or more. The U-2 is constrained by regulations restricting pilots to 12 hr. in the cockpit. U-2 pilots also are required to wear pressure suits and have reported increased instances of the “bends” after long-duration missions supporting Afghanistan operations. Without hydraulics, the U-2 is notoriously complex to fly, with pilots having to muscle against strong winds to and from altitude. Landing the aircraft, which was designed with extreme lift qualities, is treacherous.

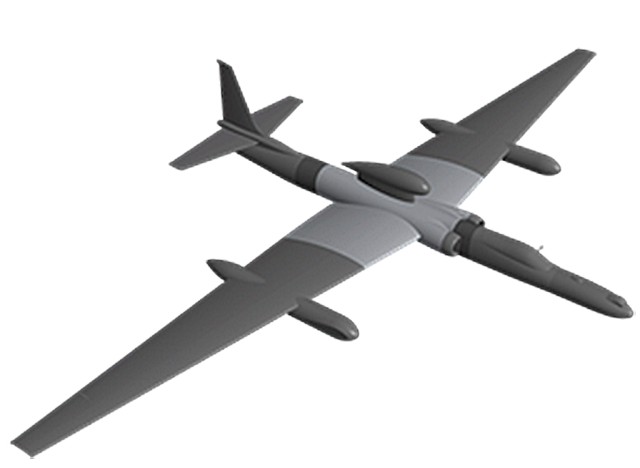

But Lockheed Martin says it can “unman” the U-2 for far less than the cost of the Global Hawk upgrade program. A newly crafted design (see image) will cost about $700 million, to optionally man three U-2s and provide two ground stations. The ground stations are compact racks and processors, so they can be operated virtually anywhere, according to a Lockheed Martin official. Once developed, flyaway cost is $35-40 million.

This design calls for the addition of a new centre wing-box that will fit between the metal wings and extend each by 10 ft. It also will provide space behind the cockpit for connecting cables into the aircraft’s actuators. “The pilot could electronically turn off the actuators and it is just like you have today, it is flying by cable,” the Lockheed official says. The design is intended to leave the cockpit untouched to allow for manned operation.

Landing could be made more predictable with the unmanned system. “As a prior U-2 pilot, I always thought this was going to be an aviation challenge. When I looked to our avionics engineers, they almost scoffed at me. . . . They said, ‘We’ve already done it—landing [an unmanned aircraft] on a pitching and rolling carrier,’ . . . and this is far easier,” the Lockheed official says. “This would be more safe, the reason being the failure modes.”

For example, in cases where pilots encounter full nose-up or down trim, they are required to apply roughly 75 lb. of pressure to the stick to maintain flight, which can be challenging for pilots in pressure suits, especially toward the end of a long mission. “Even if you are a pilot in the airplane and you have a full nose-up or a full nose-down trim failure, you can engage the autopilot and let it fly all the way down and to the landing,” the Lockheed official says. “The actuators would handle those loads easily.”

The additional space offered by the centre wing-box also could house a full-motion video sensor, the official says. Use of the wing-box will avoid a redesign to the tail that a wing extension could require. This design has been updated since Lockheed submitted a concept in 2012, which called for 140-ft. composite wings optimised for fuel carriage.

To date, Lockheed has simply completed preliminary design work. However, the proposal could whet the appetite of some lawmakers leery of retiring the U-2; with the last of the aircraft rolling off the production line in 1989, their structural lives are intact. And there is some risk associated with upgrading the Global Hawk.

Still, the Pentagon has been fickle in its high-altitude reconnaissance plan; in 2012, it proposed killing the Global Hawk Block 30 and keeping the U-2 as the workhorse intelligence collector. That was overturned this year. “I don’t see DOD reverse-reversing themselves,” said one congressional staffer, noting that another switch would likely irritate lawmakers.

Whichever platform wins out to handle the Air Force’s high-altitude reconnaissance needs, it will only be one element of a larger architecture. Both U-2 and Global Hawk are standoff platforms.

Image: Lockheed Martin Concept

Source: Aviation Week