The Defense Intelligence Agency conducted the first Black Dart exercise in 2002 under a veil of secrecy, and the annual event stayed veiled through 2013. Now run by the Joint Integrated Air and Missile Defense Organization (abbreviated JIAMDO and pronounced “jye-AM-doe), Black Dart’s existence was revealed in 2014, and select media were invited for a day last year “just to let everybody know that the Department of Defense is aware of this problem, we’re concerned about it and that we’re working on it”.

Black Dart 2015 will feature tests of 55 systems brought to Point Mugu at their own expense by an assortment of military units, government agencies, private contractors and academic institutions.

JIAMDO’s $4.2 million budget for the event covers the cost of running the Point Mugu range and providing a small fleet of “surrogate threat” drones. For five hours each day, Gregg’s Black Dart team will fly up to six drones at a time over the range while participants test radars, lasers, missiles, guns and other technologies they think the military might use to detect and kill or neutralize drones of all sizes.

What’s worked

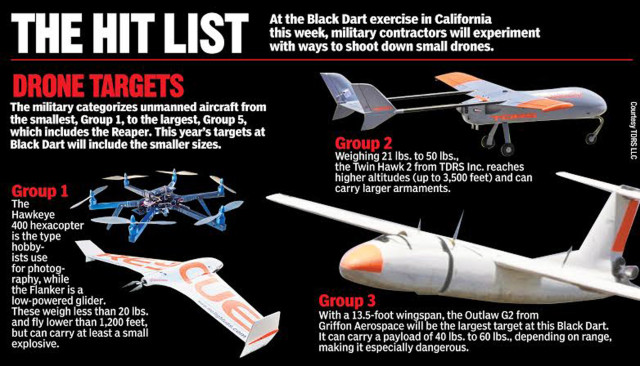

This year the surrogate threats will include three Group 1 drones — a Hawkeye 400 hexacopter, a Flanker and a Scout II — and one Twin Hawk drone from the Group 2 category (21 to 55 lbs., slower than 250 knots, lower than 3,500 feet). Six Group 3 drones, all of them 13.5-foot wingspan Outlaw G2s made by Griffon Aerospace, also will be targets.

One nice feature for contractors: Failure is an option. Black Dart isn’t an official procurement milestone, so companies can test their technologies there knowing that if they don’t work as hoped, there’s no obligation to file a report that might lead the Pentagon or Congress to cut their funding or cancel their program. They can just use the test results the way test results were meant to be used — to find out what works and fix what doesn’t.

“We should have about 1,000 people at Black Dart this year between participants, observers and support,” Gregg said, noting that the departments of Energy and Homeland Security both will send observers. But while Black Dart is no longer secret, the public isn’t invited. “It’s absolutely not an air show,” Gregg said.

Even the media won’t be allowed to see or hear about everything that goes on at Black Dart 2015. Much of what previous exercises came up with in the way of countermeasures also remains classified, said Marine Lt. Col. Kristen Lasica, spokeswoman for the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “We can’t let the enemy know what we’re going to do,” she explained.

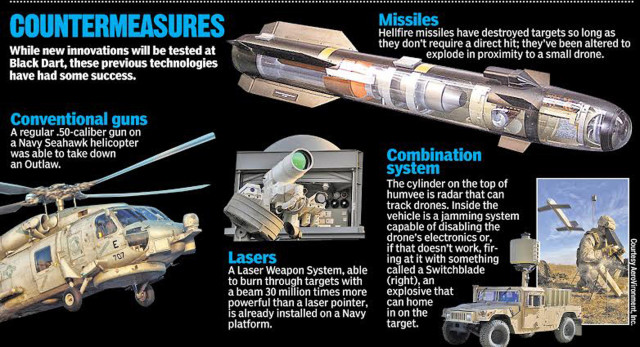

That said, some of Black Dart’s declassified successes over the years include:

- A Navy MH-60R Seahawk helicopter shot down an Outlaw surrogate threat drone with a .50-caliber gun, proving old-fashioned solutions can work fine against new-fangled threats.

- The USS Ponce, an Afloat Forward Staging Base deployed to the Middle East, today is armed with a 30-kilowatt Laser Weapon System (LaWS) that shot down an Outlaw in a test at Black Dart 2011. The futuristic weapon is also good against slow-moving helicopters and fast-moving patrol boats.