The U.S. Air Force is developing new computer algorithms to allow fighter pilots to control armed drones from inside their own cockpits. The goal of the so-called “Loyal Wingman” initiative is to pair up manned, fifth-generation stealth fighters with unmanned versions of older jets — in order to boost the lethality of both in air combat.

“You take an F-16 and make it totally unmanned,” deputy defense secretary Bob Work told an audience in Washington, D.C. on March 30. “The F-16 is a fourth-generation fighter, and pair it with an F-35, a fifth-generation battle network node, and have those two operating together.”

But the Loyal Wingman concept could also work with other fighters and drones — some already in service, other still on the drawing board. Work said that manned-unmanned teaming is the way of the future. “It is going to happen.

The Air Force Research Laboratories launched Loyal Wingman in mid-2015 with a formal request for information to the aerospace industry. “Autonomy technologies can enhance future operations and capabilities in contested and denied environments,” the RFI explained.

“Technologies are also required to seamlessly integrate the pilot and his/her aircraft with the autonomous unmanned aircraft to allow them to operate as a team for combat effectiveness.”

The idea is that a drone could fly ahead of a manned fighter in the most dangerous environments, locating and attacking targets without exposing a human pilot to potential harm.

Likewise, a drone wingman could act as a flying munitions magazine for traditionally-piloted aircraft, with the robot firing its weapons at targets the human pilot selects. Not coincidentally, the Pentagon is also developing what it calls an “arsenal plane” — a B-1 or B-52 heavy bomber modified to launch weapons at targets designated by fighter crews flying ahead of the bomber.

To be clear, the Air Force and the other military branches already operate sophisticated drones, many of them armed. In most cases, the robots’ operators sit in control stations on the ground and direct their drones via satellite.

The Army, however, has modified some of its Apache gunship helicopters with drone interfaces so that the gunships’ crews can coordinate armed drones. The Army’s rationale is that a helicopter crew is closer to the fighting than any ground-based operator can be — and the copter crew is therefore in a better position to direct an unmanned aircraft.

That same logic applies to the Air Force’s Loyal Wingman effort. Additionally, researchers are worried that, in future conflicts, a sophisticated opponent might jam long-range communications and block GPS signals from satellites, preventing operators on the ground from effectively controlling distant drones.

In the Loyal Wingman concept, a fighter pilot would issue commands to his drone wingmen via some sort of secure datalink. But the same electronic jamming that makes manned-unmanned teaming so attractive could also complicate communication between the human pilot and his robot wingmen.

For that reason, the Air Force Research Laboratories wants the robotic wingmen to be highly autonomous, requiring only minimal interaction from the human pilot. “The unmanned vehicle shall be able to operate untethered from the ground without full-time direction from the manned aircraft,” the agency stated in its RFI.

Moreover, the algorithms enabling manned-unmanned teaming should reside entirely within line-replaceable units — self-contained electronic black boxes. That way, maintenance crews can simply drop a few LRUs into, say, an old F-16 and instantly transform the jet into a drone wingman.

Embedding the new software code in just a few LRUs could be the key to AFRL meeting its tight deadline. The research agency wants to begin testing the robot wingmen as early as 2018.

Aerospace giant Boeing told Flight Global that it would bid for the Loyal Wingman contract. The Chicago plane-maker could have an advantage over potential competitors. Boeing already modifies retired Air Force F-16s into pilotless QF-16 target drones.

The same basic technology that allows a QF-16 to safely fly pre-programmed maneuvers while remaining in contact with human range operators could also transform an F-16 into a robotic wingman for combat missions.

And it’s possible the Air Force could add the Loyal Wingman LRUs to other plane types. Old F-15s, for example. More intriguingly, the flying branch could develop new unmanned aerial vehicles to act as robot wingmen.

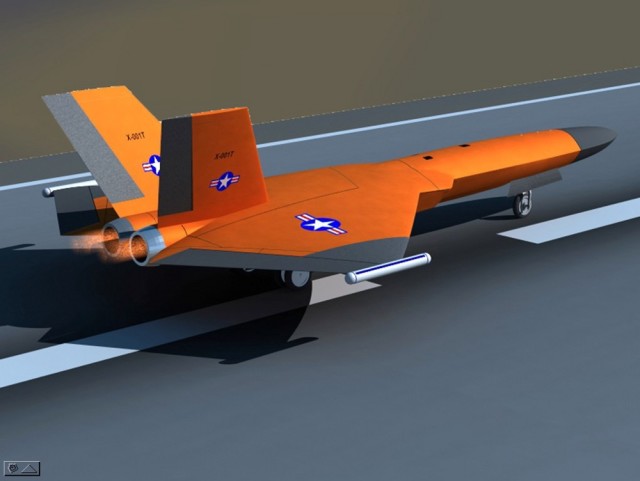

For example, cadets at the Air Force Academy in Colorado recently completed basic design work on a stealthy target drone that could fit nicely in the Loyal Wingman construct.

The Fifth Generation Aerial Target sports a simple delta wing and uses the same J85 engines that propel the T-38 trainer. The stealthy drone would possess “superior level-flight characteristics” and “superior stability characteristics,” according to one 2011 academic paper.

Add weapons and the Loyal Wingman LRUs and you’ve got a drone fighter boasting some of the same stealth attributes as the manned fighter controlling it — an obvious advantage in combat.

Source: War is Boring