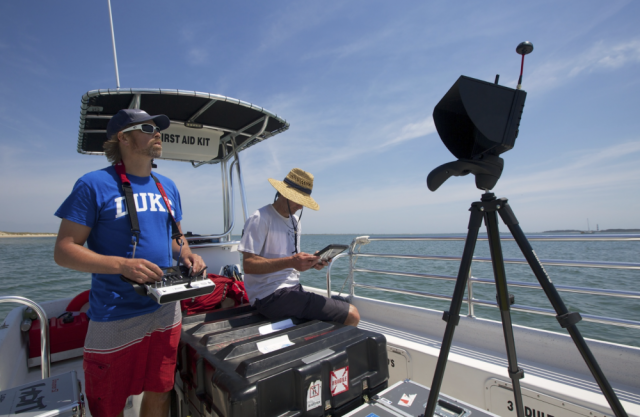

David Johnston, assistant professor of the practice of marine conservation ecology at Duke University, is currently implementing drones to study coastal waterways.

David Johnston, assistant professor of the practice of marine conservation ecology at Duke University, is currently implementing drones to study coastal waterways.

“At the Duke Marine Lab, we are working on applications that use drones to study various aspects of the marine environment ranging from coastal erosion to changing coastal habitats to counting sea turtles and sharks,” Johnston said.

Johnston serves as the executive director of the Marine Conservation Ecology Unmanned Systems Facility, which received approval from the Federal Aviation Administration to use unmanned aerial vehicle technology in September 2015. Since then, researchers at the facility have worked in improve their use of drones.

Johnston noted that the use of the drones has eliminated previously inefficient and costly methods of data collection. Drones are nicely balanced tools that optimize accuracy and efficiency, he said.

“They fill this gap between walking on the shoreline to [collect data] traditionally and being in the air with occupied aircraft or satellite,” he said. “The on-the-ground research takes a lot of time, and the aircrafts and satellites are hard to task. The drones are in the middle.”

The Marine Conservation Ecology lab uses a variety of different sensor-equipped drones and cameras that allow them to collect and quantify data. These include “fixed-wing” drones resembling little airplanes as well as “multi-rotor” resembling mini-helicopters, Johnston explained.

Many applications of drones in marine science, notably the use of drones to track shark movements at beaches, are currently being considered

However, the research has illuminated a number of complications.

“We have to deal with the murkiness and turbidity of the water, and with the tide and changing depths of the water,” Johnston said. “We have to deal with things like glare when the sun is high. There are also regulatory limitations that prohibit flying beyond our line of sight.”

Martin Benavides—a University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill graduate student who has worked with the Duke researchers—noted that weather can make it difficult for accurate shark monitoring.

“[Drones] can’t fly in high winds, and images can be easily obscured in bad weather,” Benavides said. “But we are working to get a better handle on the technology given these constraints.”

Benavides also explained that sharks are particularly difficult to track because of their speed and movement patterns. Patrick Halpin—associate professor of marine geospatial ecology—noted that the drones’ flight time could also be a limitation. “Battery life on the systems right now is getting better, but the ability to do long term monitoring is still challenging,” Halpin said. “As the technology gets better and the battery life gets better the applications will widen.”

Despite all of the limitations and challenges that the scientists have faced, their use of drones has made strides. Johnston noted that the group has had success using drones to count sea turtle populations and investigate the depth of water in Costa Rica. In addition, they have used it to study seals and seal pups in Canada. “We have also been able to use [the drones] here in the coastal waterways of North Carolina to measure the structure and features of barrier island beaches,” Johnston said.

He noted that the group still maintains high expectations for drone applications as they did when they first had the idea to incorporate the technology into their research. “We saw the promise of the technology and the next step was to start understanding the limitations,” Johnston said. “I think people are starting to realize that there are more and more opportunities for [drones], some of which aren’t marine science related.”

Source: The Chronicle – Duke University