Increasing numbers of drones in the sky raises the risk to people and property below being hit when those devices have mechanical problems. That’s why NASA researchers are building technology to help drones automatically spot the best places to crash-land without hurting anyone on the ground.

A team at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, has developed a technology called Safe2Ditch to address the problem. Its small size, light weight and low power requirements allow Safe2Ditch to be deployed on even small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) and provides an added layer of safety for commercial operations.

“A lot of drones have limited reliability because they have to be low cost to be profitable,” said Lou Glaab, a mechanical engineer and assistant branch head at the center. “You can’t have million-dollar aircraft delivering packages for Amazon.”

Referring to the 2009 United Airways jetliner piloted by Chesley Sullenberger that successfully ditched with no loss of life in the Hudson Bay after taking off from a New York city airport, Glaab said what UAS need is “an electronic Captain Sullenberger.”

Toward that end, the husband-and-wife team of Lou and Trish Glaab—a software engineer and aerospace technologist—developed Safe2Ditch, a system combining the technical monitoring capabilities of small UAS with a database of safe landing zones along the drone’s flight path.

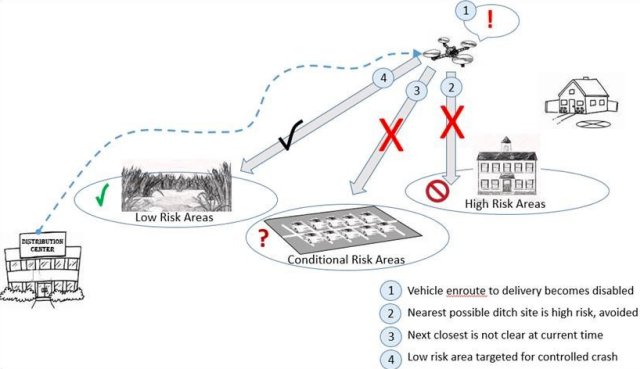

Unlike a manned aircraft, a drone has no pilot to make decisions in in an emergency situation, Lou Glaab said. Safe2Ditch is designed to work autonomously because there’s usually not enough time to engage a person in the decision-making process. It taps into the aircraft’s monitoring system, sensors and onboard autopilot to guide it to a safe landing.

As Trish Glaab explained, the database used for the technology must be flexible and conditional in determining the best spot for a landing.

“Where are people typically not going to be? Where can you not go? What hours do you have to avoid a schoolyard? Where are the wet or forested areas you prefer to avoid?” she asked. “It has to be intelligent enough to keep from hurting anyone.”

The software uses complex selection logic to understand how much time the drone has before it must land and takes its performance characteristics into consideration. It can even be programmed to know how much area is need for a fixed-wing UAS landing as opposed to a rotorcraft landing.

Because Safe2Ditch is designed for small, low-cost UAS, the Glaab’s goal is to make their system affordable to the average drone pilot. They’re designing it with inexpensive components and aiming for a maximum price point of $500.

Based on eight test flights, the technology has successfully spotted safer landing zones like swamps or drainage ditches to crash instead of on top of people’s cars, Glaab said.

She first got the idea for the technology in 2015, and received just under $10,000 from NASA to work on it. The initiative comes as businesses increasingly use drones for things like inspecting rooftops or power lines, raising the risk of in-flight mechanical and software problems that could put people below and the drones themselves in danger.

“These companies want to potentially send dozens [of drones] at a time,” Glaab said, referring to businesses like Amazon that want to put entire fleets of drones aloft to deliver orders to customers.

Many companies like China-based drone maker DJI install drones with software that helps the devices sense and avoid obstacles while in flight. But these technologies are not designed for emergency situations, Glaab explained.

“No one wants to think about it,” she said of potential drone crashes. “People are much more interested in the capabilities” and less so in “what happens when the thing is going down.”

The software links on-board drone components like batteries and motors to monitor their health. The goal is to identify when something on the drone goes haywire and, if so, put the drone in a sort-of crash-landing mode.

When triggered, the software checks a pre-installed database of nearby safe zones that it can then pilot itself toward. Big airlines already use such a national database for emergencies.

NASA’s crash-landing software also incorporates software developed from Brigham Young University researchers that lets drones recognize and avoid objects on the ground using on-board cameras, she explained.

Still, NASA’s technology is far from finished.

For instance, Glaab’s team must manually upload the safe-landing database in the drones they test for each location. Although not a laborious process, she said, it is an extra step.

Eventually, it may be possible for the drones to connect wirelessly to a national database of safe landing zones, but that’s unlikely to be anytime soon.

Glaab is still refining the drone technology and plans on doing more test flights this summer.In the future, the Glaabs see the potential for manned aircraft to be equipped with Safe2Ditch, enabling an airplane with a disabled pilot to be safely landed autonomously. The space agency does not plan to sell the technology, she said, but instead hopes to license it to drone companies.

Images: NASA Langley Research Center

Source: Fortune