Sources told the South China Morning Post that more than 30 military and government agencies have deployed birdlike drones and related devices in at least five provinces in recent years.

One part of the country that has seen the new technology used extensively is the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in China’s far west. The vast area, which borders Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, is home to a large Muslim population and has long been viewed by Beijing as a hotbed for separatism. As a result, the region and its people have been subjected to heavy surveillance from the central government.

The new “spy birds” programme, code-named “Dove”, is being led by Song Bifeng, a professor at Northwestern Polytechnical University in Xian, capital of northwestern China’s Shaanxi province. Song was formerly a senior scientist on the J-20 stealth jet programme and has already been honoured by the People’s Liberation Army – China’s military – for his work on Dove, according to information on the university website.

Yang Wenqing, an associate professor at the School of Aeronautics at Northwestern and a member of Song’s team, confirmed the use of the new technology but said it was not widespread.

“The scale is still small,” compared to other types of drones in use today, she told the South China Morning Post.

“We believe the technology has good potential for large-scale use in the future … it has some unique advantages to meet the demand for drones in the military and civilian sectors,” she said.

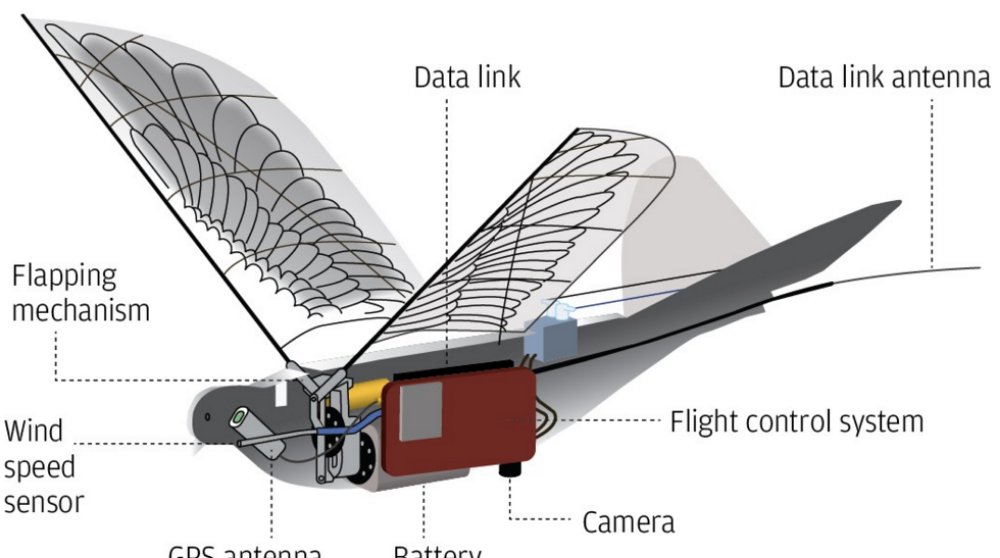

Unlike unmanned aerial vehicles with fixed wings or rotor blades, the new drones actually mimic the flapping action of a bird’s wings to climb, dive and turn in the air.

Another researcher involved in the Dove project said the aim was to develop a new generation of drones with biologically inspired engineering that could evade human detection and even radar.

The machines in China’s current robot flock replicate about 90 per cent of the movements of a real dove, the person said, adding that they also produce very little noise, making them very hard to detect from the ground, and are so lifelike that actual birds often fly alongside them.

The team conducted almost 2,000 test flights before deploying the drones in real-life situations, said the researcher, who asked not to be named due to the sensitivity of the programme.

One experiment in northern China’s Inner Mongolia involved flying the birds over a flock of sheep – animals that are well known for their keen sense of hearing and ability to be easily spooked. The flock paid no attention whatsoever to the drone flying above, the person said.

Birds are incredibly efficient fliers. The bar-tailed godwit, for instance, despite weighing only 290 grams (10 ounces) flies 11,000km (6,800 miles) non-stop from Alaska to New Zealand every autumn. The epic journey takes just eight days.

In comparison, the Dove drones weigh 200 grams, have a wingspan of about 50 centimetres (20 inches), and can fly at speeds of up to 40km/h (25mph) for a maximum of 30 minutes.

Each machine is fitted with a high-definition camera, GPS antenna, flight control system and data link with satellite communication capability. The flapping mechanism comprises a pair of crank-rockers driven by an electric motor, while the wings themselves can deform slightly when moving up and down, which generates not only lift but also thrust to drive the drone forward.

Specially designed software helps to counter any jerky movements to ensure the on-board camera achieves sharp images and stable video.

The Dove drones’ ability to seemingly melt into the background has attracted a lot of interest in military and government circles.

Professor Li Yachao, a military radar researcher at the National Defence Technology Laboratory of Radar Signal Processing in Xian, said the movement of the Dove’s wings was so lifelike it could fool even the most sensitive radar systems.

The use of camouflage – perhaps even real feathers – on the drone’s outer body could distort the radar signature still further, he said.

Aware of the dangers such stealth drones pose to conventional detection systems, radar scientists have been looking at new ways to spot and track small, low-altitude targets flying at slow speed.

These include the holographic radar, which is capable of producing three-dimensional images of flying objects and has been hailed as a significant step forward in detection technology.

However, “there is no guarantee” that even a holographic radar – or any of the other new technologies in development – would be able to detect a drone with a wing-flapping pattern that was almost identical to those found in nature, and “especially if it was surrounded by other birds”, Li said.

“It would be a serious threat” to air defence systems, he said.

According to a recent government document seen by the Post, China’s military has tested the Dove system and is impressed with it.

An evaluation of the system by an unspecified military research centre concluded that the drone, with its ability to stay in the air for more than 20 minutes and travel 5km, had “practical value”.

Gan Xiaohua, chief engineer at the PLA Air Force Equipment Research Institute in Beijing, said Dove’s unique design meant it could convert electrical power into mechanical force with “high efficiency”.

It is “the world’s only bionic micro drone capable of carrying out a mission all by itself”, he was quoted as saying in the government document.

Although the Post was unable to reach project leader Song for comment, in an April interview with the Chinese academic journal Aeronautical Manufacturing Technology, he confirmed that Dove and other devices had been deployed in Xinjiang and other provinces.

“The products … have stimulated change and development in sectors including environmental protection, land planning … and border patrol,” he was quoted as saying.

Despite the technological advances made on the Dove project, China’s bird-like drones were still far from perfect, Song said.

Besides being unable to travel long distances or maintain course in strong winds, their performance could be badly hampered by heavy rain or snow, he said.

Also, the absence of an anti-collision mechanism meant the drones were prone to crash into things when flying at low altitude, while their electronic circuitry was vulnerable to electromagnetic disturbance.

Nevertheless, researchers were working hard to resolve these problems, and with advancements in artificial intelligence technology, such as deep learning, Song said he hoped the next generation of robotic birds would be able to fly in complex formations and make independent decisions in the air.

When that day comes, the Doves would be able to “match or surpass the intelligence of creatures found in nature”, he said.

Source: South China Morning Post