A high-level delegation of Chinese military mapping experts visited a Cambodian naval base in December, three weeks before a huge Chinese surveillance drone crashed in the adjoining province, according to a leaked document obtained by the ABC.

But the crashed drone has revived speculation about China’s role in the South-East Asian nation after reports emerged last year of a 30-year deal to host Chinese troops, weapons and supplies at the Ream naval base.

When US Vice-President Mike Pence raised the alleged secret base, there were howls of denial from Khmer leaders.

However, the document obtained by the ABC outlines close cooperation between the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) and China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), some of which has been kept out of the public eye.

“To enhance military cooperation between armed forces between China and Cambodia, a six-member Military Surveying & Mapping Delegation headed by Major General Song Ming Wu, deputy rector of Information Engineering University of PLA, will visit Cambodia from December 20 to 24,” wrote Colonel Li Ningya, China’s defence attaché in Cambodia.

Colonel Li asked Cambodia to prepare “VIP rooms” in the airport, a police convoy and interpreters.

The English translation of the schedule was obtained by the ABC from a source who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the issue and was verified by a second source with knowledge of the visit.

The schedule suggested visits to “investigate Ream base”, and to the islands of Koh Takiev — home to a small Cambodian naval outpost— and Koh Poulu Wai — the site of the 1975 Mayaguez Incident, where the Khmer Rouge captured a US merchant vessel and sparked a rescue that is considered the last battle of the Vietnam War.

The PLA delegation also planned to meet with 20 Cambodian troops who recently completed a six-month “surveying, mapping and navigation training class” in China, before finishing the trip with a look at a “satellite navigation and positioning reference station” in Siam Reap province.

“The letter suggests a level of normalisation for this kind of engagement,” said John Blaxland, a professor at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the Australian National University.

“It’s not clear whether these are sites that are yet to be formally incorporated as PLA facilities, or ones that are on the cusp of becoming so or ones that are being investigated for being included as PLA facilities,” said Mr Blaxland, a former Australian defence attache in Thailand.

Killer ‘Rainbows’ and buckets of gold

The secret PLA visit came just weeks before a military-grade Chinese-made drone parachuted gently — but apparently accidentally — down into a field in southern Cambodia, creating a short-lived frenzy of speculation about what it was doing there.

“We don’t know where the drone came from,” Air Force Command spokesman, Prak Sokha, told the Phnom Penh Post newspaper.

He said Cambodia had contacted the Chinese Government, the Chinese company developing the US$3.8 billion “resort” site and the Chinese manufacturer of the drone.

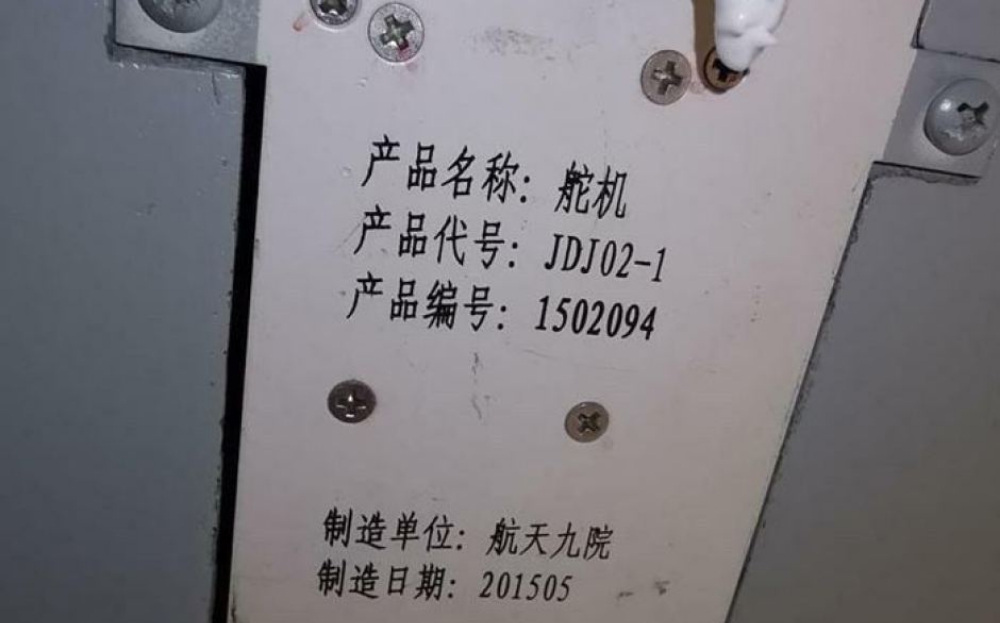

Chinese characters on the side of the crashed drone make its origins clear.

It is a CH-92A (or close variation) produced by the China Aerospace Science & Technology Corporation. Or to be even more embarrassingly specific, it’s drone #1701002, with components manufactured in 2014 and 2015.

“This appears to contradict the Cambodian Government’s recent promises that it would not allow Chinese military presence within the country,” said Kelvin Wong, the unmanned systems editor at Jane’s Group UK.

The “CH” stands for “cai hong”, meaning “Rainbow” in Mandarin.

The CH-92A has a range of 250 kilometres and can fly for 8 to 10 hours but is actually at the smaller end of the range, with larger Rainbows carrying weapons payloads of more than 300 kilograms.

China has sold drones to militaries including Indonesia, Myanmar, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, United Arab Emirates and Nigeria. But not to Cambodia, as far as anyone’s aware.

Cambodia’s hyper-corrupt military barely has a conventional air force, with its fighter jets non-functioning and its helicopters mostly used to ferry VIPs around the kingdom.

Media reports from journalists at the crash site in Cambodia’s southern Koh Kong province, are that the drone was about 5 metres long, with a wingspan of 9.7 metres.

There’s no publicly-acknowledged price list for these machines, but two sources told the ABC such a drone would cost between US$200,000 and US$300,000 ($299,000 and $448,000)

Typically, this type of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) is launched either with an initial rocket boost or is flung off the back of a speeding truck, as seen in the video below.

https://youtu.be/Acj0LZP44g4

It can land on wheels or skid down to earth on bumpers (also seen in the video), but this one appeared to have been set up deliberately for a parachute landing, according to one expert.

And this invites intrigue.

“What this tells us is that this UAV is not operating from an airport,” Mr Wong, the Singapore-based drone expert, said.

He is hesitant to speculate about exactly who was likely flying the craft.

“What I can say is that whoever was operating it intended to operate it very discreetly,” said Mr Wong.

In recent years, Cambodia has snubbed Western nations such as the US and Australia, in favour of closer political and military ties with China.

Beijing has returned the favour with buckets of cash, mostly in the form of donated equipment, grants and cheap loans.

While some of this cooperation is conducted in the open, some aspects — like the recent PLA mapping training — are kept quiet.

A surveillance drone such as the CH-92A would be just the sort of technology the Cambodians might have been training on with the PLA.

“Not saying that’s happening, but yes, this would be an ideal platform for training,” Mr Wong said.

The ABC’s calls and text messages to Air Force Command spokesman Prak Sokha went unanswered.

“There may not be a direct correlation between the timing of these two incidents [the PLA visit and the drone crash] but they’re probably related back in Beijing, in terms of the plan for managing development of capabilities inside Cambodia,” Mr Blaxland said.

Controlling Asia’s ‘jugular vein’

While much interest has focused on a secret naval base in Cambodia, another site listed on the PLA schedule could be just as important for China’s long-term strategic efforts in the region.

The ancient capital of Siem Reap is home to the tourist attraction Angkor Wat and other magnificent ruins, but somewhere in the province exists a “satellite navigation and positioning reference station”.

“This is actually potentially quite a significant site for China, operating near Siem Reap,” Mr Blaxland told the ABC.

Mr Blaxland said it might be linked to China’s development of the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System (BDS) as an alternative to the US-controlled Global Positioning System (GPS).

Access to a satellite station in Cambodia — perhaps combined with deep water ports further south — would be a handy asset for China.

“It’s also a site from which they [China] can exert influence over and beyond the Malacca Strait … [which is] essentially the north-east Asia states’ jugular vein, and I mean here China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan,” Mr Blaxland said.

Flashpoints in the East China Sea, South China Sea, Taiwan or North Korea could potentially pit China and the United States against each other, in which case control of oil and other cargo through the Malacca Strait would become a key strategic advantage, said Mr Blaxland.

The new Macau or a secret naval base?

Location is also why the Chinese drone caused such a sensation when it crashed on January 17.

It landed about 7 kilometres from a controversial Chinese development that has also been cited as a potential Chinese military base in disguise.

Journalists at the crash site, in Cambodia’s southern Koh Kong province, report the drone was about 5 metres long.

Journalists at the crash site, in Cambodia’s southern Koh Kong province, report the drone was about 5 metres long.

The Cambodian Government gave Union Development Group (UDG) a 99-year lease to develop a “resort” on 36,000 hectares in Koh Kong province, a plot of land that accounts for 20 per cent of Cambodia’s entire coastline.

Given the 3.3-kilometre-long airstrip (the longest in the country), plans for a deep-water port and almost total lack of tourists, there’s hot debate whether it really is a resort or cover for a dual-use civilian-military facility.

“Maritime infrastructure investment is inherently dual-use and is capable of furthering both legitimate business activities and military operations,” said Devin Thorne and Ben Spevak in their 2017 report Harbouring Ambitions, which looked at the UDG project.

“The investments described above are both serving China’s national security interests and altering the strategic operating environment of the United States and its allies …,” said the authors of the report, published by security analysts C4ADS.

Those US allies, of course, include Australia.

CH-92A has a range of 250 kilometres and can fly for 8-10 hours

CH-92A has a range of 250 kilometres and can fly for 8-10 hours

America was miffed when Cambodia asked for its help developing the facility, then abruptly backtracked in favour of Chinese military assistance.

Cambodian officials were unusually forceful in their rejection of reports of a 30-year deal to host the PLA — at times seeming to be exhausted by the need to explain.

“We have declared again and again that there is no agreement that [approves] any location for Chinese military to operate in Cambodia,” a Ministry of Defence spokesperson, Chhum Socheat, told Voice of America in July.

“We have said enough.”

However, Mr Blaxland said denials about military bases, crashed drones and secret visits are to be expected when such a sensitive relationship is at stake.

“I think the denials will continue … [Cambodia will] be looking to cooperate with China to hush up what’s happened and explain it away in anodyne terms,” he said.

Top Photo: Khmer Times

Source: ABC