To support search-and-rescue efforts, one group of innovators in Europe has succeeded in harnessing the power of drones, AI, and smartphones, all in one novel combination. Their idea is to use a single drone as a moving cellular base station, which can do large sweeps over disaster areas and locate survivors using signals from their phones.

AI helps the drone methodically survey the area and even estimate the trajectory of survivors who are moving.

The team built its platform, called Search-And-Rescue DrOne based solution (SARDO), using off-the-shelf hardware and tested it in field experiments and simulations. They describe the results in a study published 13 January in IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing.

“We built SARDO to provide first responders with an all-in-one victims localization system capable of working in the aftermath of a disaster without existing network infrastructure support,”

explains Antonio Albanese, a Research Associate at NEC Laboratories Europe GmbH, which is headquartered in Heidelberg, Germany.

“The intuition behind it is to adapt the classical cellular multilateration technique, which is based on simultaneous target distance estimates from several anchors, for example, base stations, to the case when only a single, moving anchor is available.”

The point is that a natural disaster may knock out cell towers along with other infrastructure. SARDO, which is equipped with a light-weight cellular base station, is a mobile solution that could be implemented regardless of what infrastructure remains after a natural disaster.

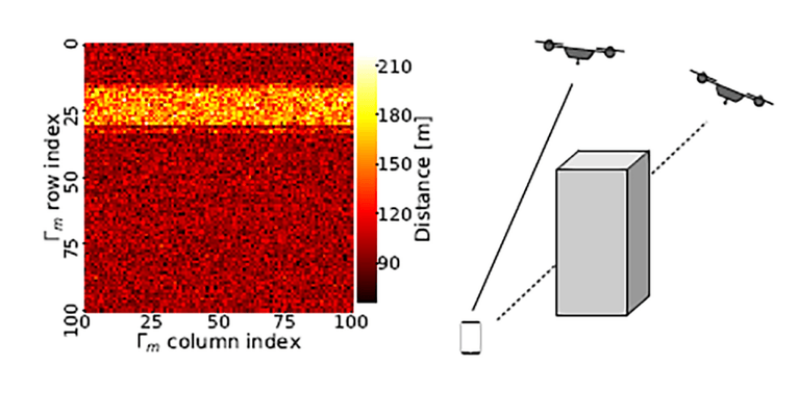

To detect and map out the locations of victims, SARDO performs time-of-flight measurements (using the timing of signals emitted by the users’ phones to estimate distance).

A machine learning algorithm is then applied to the time-of-flight measurements to calculate the positions of victims. The algorithm compensates for when signals are blocked by rubble.

If a victim is on the move in the wake of a disaster, a second machine learning algorithm, tasked with estimating the person’s trajectory based on their current movement, kicks in—potentially helping first responders locate the person sooner.

After sweeping an area, the drone is programmed to automatically maneuver closer to the position of a suspected victim to retrieve more accurate distance measurements. If too many errors are interfering with the drone’s ability to locate victims, it’s programmed to enlarge the scanning area.

In their study, Albanese and his colleagues tested SARDO in several field experiments without rubble, and used simulations to test the approach in a scenario where rubble interfered with some signals. In the field experiments, the drone was able to pinpoint the location of missing people to within a few tens of meters, requiring approximately three minutes to locate each victim (within a field roughly 200 meters squared. As would be expected, SARDO was less accurate when rubble was present or when the drone was flying at higher speeds or altitudes.

Albanese notes that a limitation of SARDO–as is the case with all drone-based approaches–is the battery life of the drone. But, he says, the energy consumption of the NEC team’s design remains relatively low.

The group is consulting the laboratory’s business experts on the possibility of commercializing this tech. Says Albanese:

“There is interest, especially from the public safety divisions, but still no final decision has been taken.”

In the meantime, SARDO may undergo further advances. “We plan to extend SARDO to emergency indoor localization so [it is] capable of working in any emergency scenario where buildings might not be accessible [to human rescuers],” says Albanese.

Source: IEEE Spectrum