Keeping Sydney supplied with water means watching over many kilometres of pipeline. Thanks to drones and great troves of data, this company is making that task easier.

The biggest city in Australia gets 80 per cent of its water delivered through two pipes running above ground from a dam created at a narrow gorge in the Warragamba River.

Ensuring such vital infrastructure remains in top condition is a substantial task: at a length of more than 27 km, there is plenty of pipeline to succumb to cracks, leaks or corrosion. It should be no surprise, then, that the inspection and monitoring of this conduit — called the Warragamba Pipeline — is important and difficult work.

Traditionally, doing that work would require staff to go out in the field for manual inspections — a task that is both time-consuming and labour-intensive.

Enter Australian UAV, or AUAV, a Melbourne-based drone-service business that specialises in surveying, inspection and 3D modelling.

“This project was a challenge,” admits AUAV Director James Rennie. “It was definitely pushing the boundaries of large-scale data capture at a micro, micro scale.”

Over its past eight years of operation, AUAV has conducted more than 50,000 drone flights and become highly adept at handling large amounts of data. And modelling the Warragamba Pipeline meant handling an enormous amount of data.

“We ended up with 118,000 photos and that’s all at just over 20 megapixels,” Rennie said. “We’re talking terabytes of data.”

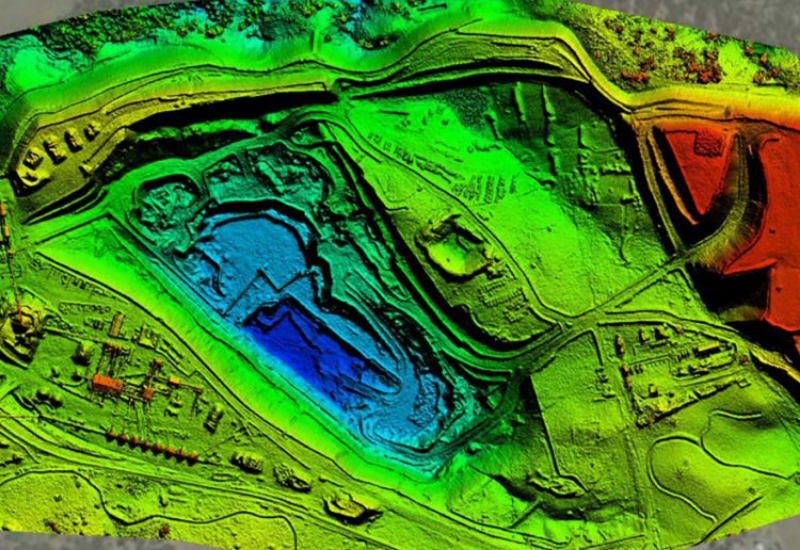

All that data was used to create a 3D model of the entire length of the pipeline that is accurate to a submillimetre level.

“Which is, in hindsight, a little bit bonkers,” Rennie said. “Really the technical challenges for this project were the volume of the data. So, projects on that scale, there aren’t too many of them around, and the ability to absorb that amount of data and then produce something which is incredibly useful for the client has been quite valuable.”