Northrop Grumman is going to repurpose four ex-U.S. Air Force RQ-4 Global Hawk drones as Range Hawk surveillance platforms to monitor hypersonic missile tests.

The change of role for the drones is part of the Air Force’s efforts to divest itself of the oldest Global Hawks and reflects the rapidly growing importance of the many hypersonic weapons now in development in the United States, across the services.

The official transfer of the four Block 20 Global Hawks under the Pentagon’s Sky Range program took place last week. The drones were transferred from Grand Forks Air Force Base, North Dakota, which is home to the 319th Reconnaissance Wing, flying the RQ-4 from there as well as with squadrons and detachments at different operating locations around the globe. The drones were then handed over to Northrop Grumman’s Grand Sky location, a separate facility close to Grand Forks that’s dedicated to unmanned aircraft development and testing.

NASA RQ-4 Global Hawk, U.S. civil registration code N874NA, after receiving modifications to support the Sky Range program

Now they are back with the manufacturer, the Global Hawks will have new equipment installed for their missile-testing mission and will then be flown to facilities either on the east coast or the west coast, to take part in hypersonic missiles trials.

Previous reports indicated that the Range Hawks would be used over the Pacific test ranges, which have already hosted various hypersonic missile tests, including of the AGM-183A Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon, or ARRW, which set to be the Air Force’s first operational air-launched hypersonic missile.

B-52H carrying prototype of the AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon, or ARRW, for its first captive carry flight, in June 2019.

Earlier accounts suggested that some of the Global Hawks redirected to the Sky Range program would be drawn from NASA’s test fleet, although the latest reports indicate that the first four, at least, are from Air Force stocks. However, NASA Global Hawks have supported hypersonic testing in the past and the agency has already been working with Northrop Grumman on Sky Range. At least one NASA RQ-4s had been adapted for Sky Range trials as of last year, based on an image released by the Air Force. It could also be the case that this drone, with the U.S. civil registration code N874NA, is being used only for experimental work that will inform the production versions of the Range Hawk.

Otherwise, it’s unclear exactly what kinds of sensors will be installed on the drones, which were previously used mainly for surveillance of ground targets and electronic intelligence gathering.

Contracting documents from 2019 explain that Sky Range, in general, is an extension of the test ranges’ telemetry and Flight Termination Systems adapted for integration into airborne platforms. The result is an asset that can be “emplaced quickly to increase operations tempo and enable coverage across extended, multi-range flight test environments.”

According to officials speaking at the handover event, new telemetry-gathering sensors will allow the drones to “look up” instead of down, suggesting a radar optimized for aerial targets will be included, as well as electro-optical sensors, perhaps including Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) and/or a multispectral telescope. These sensors will need to have considerable range, since hypersonic weapons typically travel considerable distances than many conventional missiles.

The drones will also likely be equipped with long-range datalinks to transmit telemetry from missile tests to ground stations in near-real-time. In fact, stringing multiple RQ-4s over great distances could allow them to maintain line-of-sight datalinks, even if as a backup for satellite datalinks during the very high-stakes tests. They could support other types of critical communications in remote areas, as well as range clearing and other duties.

It’s possible the adapted Global Hawks will feature some similar capabilities, at least to a limited degree, as those found on the Navy’s current NP-3D, as well as its future NC-37B range support platforms. The NP-3s have already been used to track hypersonic missiles in the past and you can read about the extensive equipment ‘fits’ found on both types here.

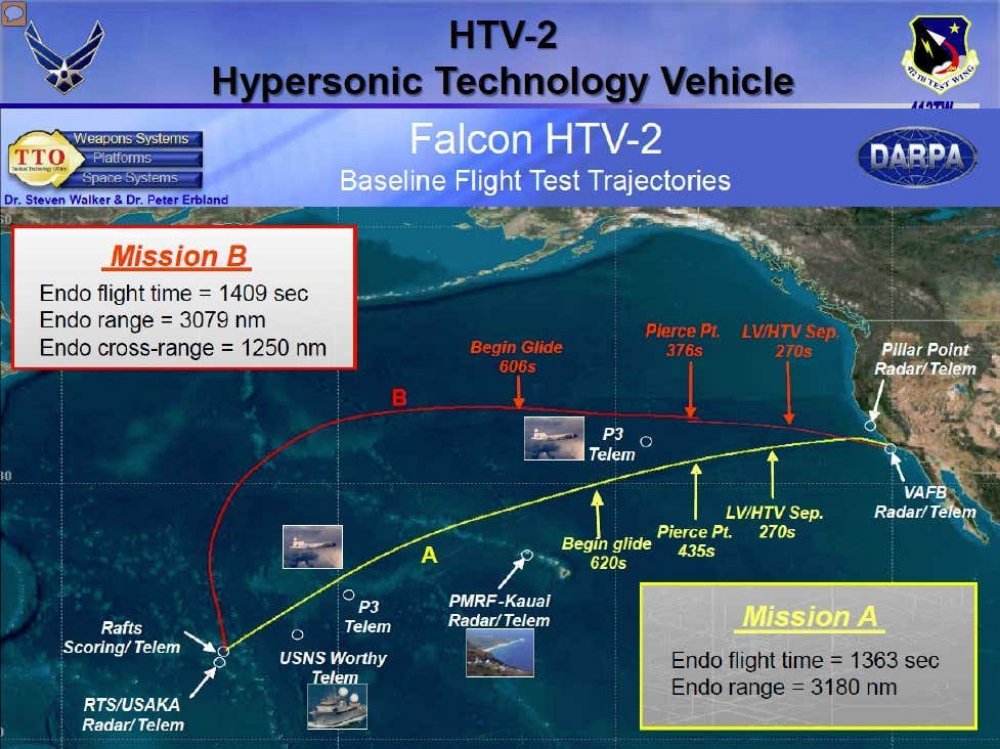

A briefing slide from one of the HTV-2 hypersonic tests, showing its path, as well as some of the land and sea assets used to monitor its flight

The RQ-4 certainly seems to lend itself to the missile monitoring role. With the ability to carry a 3,000-pound payload capability over a range of 12,300 nautical miles, the drone can perch at an altitude of 60,000 feet to observe high-flying missiles and can remain airborne for more than 34 hours if required.

“We’re going to need [remotely piloted aircraft] all the way down the range to do what a whole armada of surface vessels do today,” Major General Christopher Azzano told Air Force Magazine in 2019. “It’s going to be immensely cheaper,” he added, comparing the expected cost of drones with the missile tracking vessels typically used today.

Ultimately, it seems the Range Hawks could also complement NASA’s manned WB-57F aircraft, which are also configured to help gather data from missile tests, and which you can read more about here.

The drones will, however, require a significant amount of work to bring them back into service, according to a report from the Grand Forks Herald, which covered last week’s handover ceremony:

“Two of the large drones — they have a wingspan of 130 feet — were inside Northrop’s 35,000 square foot hangar on Wednesday, with portions of their engines exposed. The drones are scarred and battered and covered with aeronautical tape. From every side, they appear as instruments of war. They have flown missions equivalent to three and a half years of flight time.”

But once work on the first four Block 20 drones is complete, there are plans for more Range Hawks to be added to the fleet, this time using the later Block 30 models, according to North Dakota’s Senator John Hoeven. The Air Force is trying to dispose of the Block 30 drones in the next year or two, reducing its Global Hawk fleet to just the more modern Block 40 RQ-4s, at least for the immediate future.

An EQ-4 drone outside a hangar at Grand Forks Air Force Base, after concluding its final flight, on July 29, 2021. The EQ-4 was also adapted from the Block 20 Global Hawk and was equipped with the Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN)

Although the costly Global Hawks arrived in service with much-vaunted high-level surveillance capabilities, the Air Force has since called for them to be replaced by a variety of different platforms, among them “penetrating” vehicles and “fifth and sixth-generation capabilities.” You can read more about the Air Force’s plans for replacing the Block 20/30 Global Hawks with new types of stealthy platforms in this previous War Zone article.

In its Fiscal Year 2021 budget request, the Air Force had asked for approval to retire all 21 of its remaining Block 20 and Block 30 Global Hawks. That would free up additional airframes for the Range Hawk effort and perhaps also for transfer to potential export customers, some of which have shown interest in secondhand Global Hawk variants in the past.

As well as the Range Hawks, however, the Sky Range program also envisages smaller MQ-9 Reaper drones adapted as Range Reapers to gather additional data on missile launches.

Sky Range is all just one of the various efforts that are being made across the U.S. military, and elsewhere within the U.S. government, to support future hypersonic testing. So, while the Air Force might be generally unconvinced about the future of its earlier Global Hawks in their original surveillance role, the prospects for the reworked drone look much more promising in a new role monitoring the Pentagon’s various hypersonic missile tests.

Source: The Drive