The University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo is on the cutting edge of the fight against a scourge that has killed thousands of acres of ʻōhiʻa lehua trees on the Big Island.

UH-Hilo geographer and professor Ryan Perroy and his research team developed a new aerial chainsaw drone attachment that could help save ʻōhiʻa trees from the deadly fungal pathogen that causes rapid ʻōhiʻa death. The device is now being put to the test, sampling tree branch samples for diagnostic laboratory testing and other purposes.

“There have been times when we detected an ‘ōhi‘a tree suspected of infection with the pathogens responsible for rapid ʻōhiʻa death, but because of the location, it was too dangerous or problematic to send field crews out to sample it for confirmation,” Perroy said in a press release. “(The new device) has the potential to help in those types of situations.”

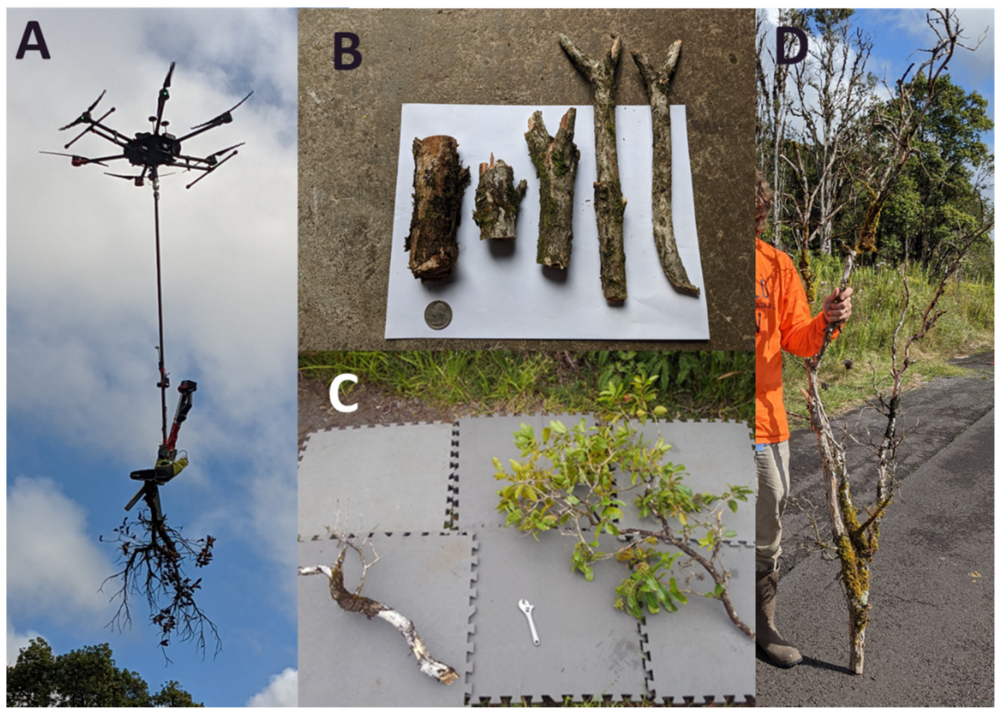

The drone attachment, named Kūkūau, consists of a small rotating chainsaw with a robotic gripper claw mounted beneath a drone and can cut and retrieve branches up to 7 centimeters in diameter. The samples are collected for diagnostic testing of forest fungal pathogens, including those responsible for rapid ʻōhiʻa death.

The device was developed in collaboration with researchers at ETH Zürich, a public research university in Switzerland; the U.S. Department of Agriculture; and R&R Machining/Welding in Hilo.

Kūkūau is the name of an ahupuaʻa (land subdivision) in the Hilo area, and is also a term for a type of crab, Metopograpsus thukuhar, or ‘alamihi in Hawaiian.

Researchers at ETH Zürich had previously developed a drone attachment capable of cutting small tree branches; however, when the UH-Hilo team used the device they found that the samples of twigs were often too small to detect fungal pathogens.

The new drone attachment consists of a rotating chainsaw with a robotic gripper claw mounted beneath the drone

In July 2019, Perroy’s team collaborated with the Swiss researchers and the Hilo welding company to develop a new drone attachment equipped to saw off larger branches.

“We successfully detected the target fungal pathogen from the collected branches and found that branch diameter, leaf presence and condition, as well as wood moisture content are important factors in pathogen detection in sampled branches,”

Perroy explained.

Rapid ʻōhiʻa death has killed hundreds of thousands of mature ‘ōhi‘a trees (Metrosideros polymorpha) throughout the Hawaiian Islands since 2014 and continues to spread. The disease is caused by two invasive fungi, Ceratocystis huliohia and Ceratocystis lukuohia, and has the potential to irreversibly change some native Hawaiian ecosystems.

None of the smallest branch samples tested positive for Ceratocystis lukuohia while 77% of the largest diameter branch samples produced positive results. The research shows that the new branch sampler, capable of retrieving the larger branches, provides the right size for a higher rate of successful diagnostic testing.

Aerial branch sampling. (A) Kūkūau branch sampler in the air following a successful cut; (B) Samples from a single branch, U.S. Quarter dollar (25 cents coin) for scale; (C) Two different collected branches, branch on the right contains healthy green leaves from a tree exhibiting partial C. lukuohia canopy symptoms; (D) >2 m tall branch collected by the Kūkūau branch sampler

Perroy is principal investigator at the UH-Hilo Spatial Data Analysis and Visualization Laboratory, a research unit applying geospatial tools to local environmental problems in Hawai‘i and around the Pacific. His group has been working on the detection of rapid ʻōhiʻa death and invasive species populations throughout forests in Hawai‘i using high-resolution cameras and other sensors carried by drones and helicopters.

The collected images and data provide managers precious time to respond to outbreaks and give scientists better information about how diseases and invasive species spread.

In 2019, Perroy won $70,000 in a competition sponsored by the National Park Service for his innovative use of drones and remote sensing devices to detect rapid ʻōhiʻa death. Throughout the past three years, he and his team have continued to hone and refine the equipment needed to conduct aerial sampling using a small unoccupied aerial system.

The research paper ‘Aerial Branch Sampling to Detect Forest Pathogens’ can be accessed here.

Source: Big Island Now