“When a company wants to start commercialising drone technology, the patent landscape can be thought of as a minefield.”

Drone technology has taken to the skies over the past twenty years in multiple areas—from applications to the military.

It seems like everyone wants their piece of the skies including meal delivery companies, insurance agencies, tech companies, and retailers.

Recently, drones have reshaped modern warfare, as shown in the war in Ukraine. Rather than risking ground troops for reconnaissance, drones are sent in their place. Drones can also be used to identify targets and guide artillery. Ukraine and Russia are leaning on both robust military drones and even commercial drones that ordinary consumers can purchase online.

But the commercial industry is also investing heavily into the technology. The US saw its first drone pizza delivery in 2016.

Now, Amazon’s ‘Prime Air’ is delivering packages in two cities with hopes to expand into more areas. With that, it is no surprise that the drone industry is estimated to reach an impressive $54 billion dollars by 2028.

However, in many industries, drone technology is still developing, and the current technology has its limitations. Compared to more traditional delivery means, drones have a limited range, can carry smaller loads, and are more susceptible to changing weather conditions.

Nonetheless, companies have been more vigorously pursuing IP protection for drone technology since the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) created a clear regulatory framework for drone use in 2015.

Before 2015, the FAA required “special permission” to operate drones, creating a major backlog in drone flying approval.

This article explores how many drone patents are being issued, who is filing for them, recent litigation relating to drone patents, and what’s next for the industry.

Drone patents are through the roof

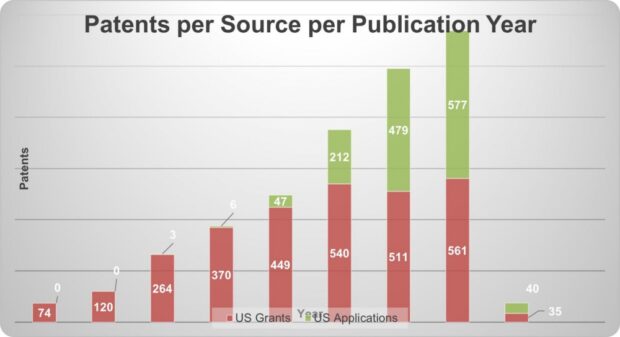

A search for the words “drone”, “UAV”, or “unmanned aerial vehicle” in the title and abstract of every issued and active patent application in the US reveals a sharp increase in drone patents since 2015. Since then, industry players have filed over 2,500 US patent applications to protect their valuable IP.

From 2015 to 2022, the number of issued patents on drone technology has skyrocketed approximately 658%.

Drones are complex systems that encompass technology from a wide range of engineering disciplines. Starting at the structure of the drone, we see mechanical and aerospace concepts such as propulsion, dynamics, and manufacturing methods.

Internally, we see many electrical and software engineering concepts at work such as telecommunications, controls, and signal processing.

It follows that the patent landscape pertaining to drones also consists of a diverse technical landscape. For example, some of the most common phrases produced by the patent search query include ‘signal’, ‘flight path’, ‘control system’, ‘autonomous’, ‘computer program’, and ‘wireless communication’. An example of the most common term ‘signal’, is the patent application US 17/466,441 filed in 2021.

In that application, Drone Go Home describes a system for monitoring the radio frequency spectrum for drone-like signals. This detection system could bode well for enforcing ‘no fly zones’, protecting privacy, and limiting drone use for nefarious purposes.

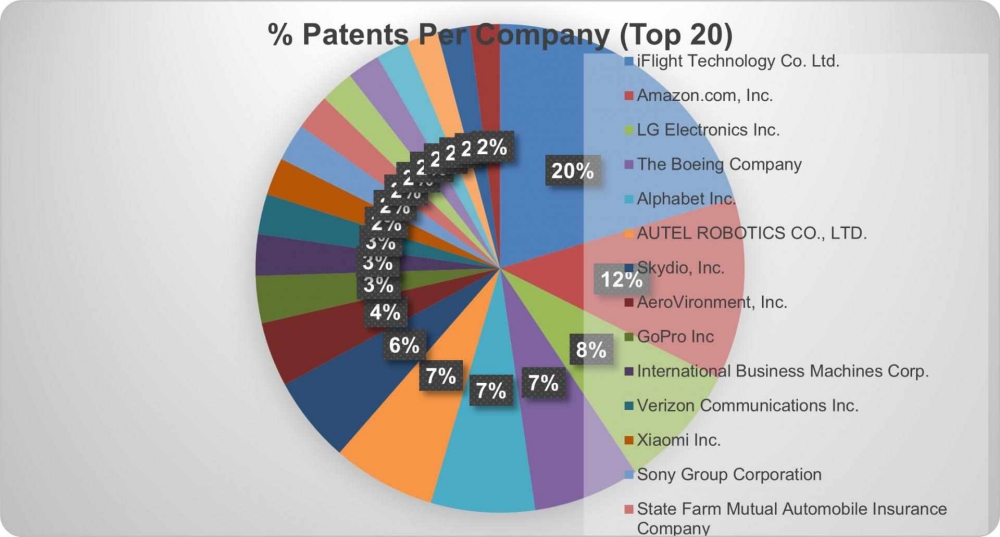

The figure below shows that many different players are actively seeking patent protection on their drone technology. Based on International Business Machines Corporation’s (IBM) recent filings, this is wide-ranging and includes software applications, 3D printing, and innovations that help people with ambulatory impairments.

IBM is already commercialising drones through its professional service ‘DroneDeploy’. Using state of the art software, IBM touts its ability to take the vast amount of images captured by a drone and stitch them together for businesses to obtain useful insights. One application for this, IBM notes, is for the agricultural industry. Farmers managing thousands of acres can use DroneDeploy software to map their land at a high resolution and even zoom in far enough to monitor individual plants.

But IBM may have even more plans for drone technology. US patent number 10,696,035, which was issued in 2020, describes a method for a swarm of drones to 3D print objects. The patent explains that, by building drones with equipment necessary to deposit material and using a centralised server, the drones can work together to build 3D objects.

Moreover, US patent number 9,863,776 describes a method for using drones to determine the safest route for individuals with ambulatory impairments. A drone could assess the risks of each route and identify the best one for an individual to proceed.

Another industry player filing for drone patents is insurance company State Farm. Not only does State Farm offer insurance for drones but, in the future, it may send drones to visit fender benders.

State Farm’s patent, US patent number 10,380,694, describes a system for notifying a drone the GPS location of an insured person’s crash site. From there the drone can collect crash data from the scene and, using the data, potentially reconstruct the crash scene before it even happened.

With everyone seeking to protect their IP, are they also enforcing it through litigation?

Since 2019, 16 separate litigations have asserted at least one of the 1,692 issued patents with either the terms ‘drone’, ‘UAV’, or ‘unmanned aerial vehicle’ in the title or abstract.

Two cases, XiDrone Systems v 911 Security Inc. and Parrot SA v QFO Labs, provide insight into the drone litigation landscape.

Case study (i) XiDrone Systems Inc v. 911 Security

XiDrone sued 911 Security alleging infringement of four patents. The patents at issue were geared towards drone defence by assessing drone threats, detecting drones, and deterring them. XiDrone alleged that 911 Security’s ‘AirGuard’ system infringed their patents. Specifically, the Airguard system detects drones by using RF sensors, specialty radars, and multiple radios in a given area. In the complaint, XiDrone stated that 911’s system has been used commercially at major sporting events and for law enforcement agencies.

During litigation, 911 filed a motion to dismiss alleging that the claims that XiDrone sought to enforce were invalid under section 101. The court declared that independent claim 1 of US patent number 10,670,696 invalid as abstract. The court found that, even though claim 1 described a system of collecting data using RF scans and sensors, it concluded with “perform a threat assessment… using at least a portion of the data”. Thus, the court found that XiDrone never claimed any particular type of assessment. Because the claim does nothing more than “process data”, the court found it directed to ineligible patent subject matter. While other claims did survive the analysis, the parties subsequently filed a joint motion to dismiss to conclude the litigation.

Case study (ii) Parrot SA v QFO Labs

QFO Labs and Parrot S.A. have been in patent litigation throughout multiple district courts, the Patent Trials and Appeals Board (PTAB), and the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. When QFO attempted to license its patents, the parties could not agree, so Parrot took to the Delaware District Court for a declaratory judgment of non-infringement.

Subsequently, QFO filed a suit of alleged infringement in Minnesota, but it was dismissed under the ‘first-to-file’ rule. Undeterred, QFO sued Parrot’s distributors, such as Amazon, Best Buy, and Target. However, those cases were stayed pending the suit with Parrot, the manufacturer.

Meanwhile, during the Delaware lawsuit, QFO asserted claims against Parrot from four different patents. Because the QFO patents are largely directed towards methods for using a controller’s accelerometers to communicate a desired position of the drone, QFO asserted that Parrot infringed their patents through its ‘tilt-to-fly’ control system. After disputing all four patents at the PTAB, some challenged claims were rendered unpatentable for obviousness, but none of the claims QFO was asserting were defeated.

But QFO did not come out of the PTAB battles unscathed, in addition to invalidating some claims, QFO disclaimed two of their asserted patents entirely. Moreover, their appeals to the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s invalidity decisions for the claims not asserted in the district court.

Then, after Markman, each district court case with Parrot and the distributors was voluntarily dismissed.

What is next?

The drone industry has seen a high number of recent drone patent filings, but, so far, a low number of litigations.

The sharp rise in issued patents shows an industry trend towards developing and adopting drones into businesses. And the vigorous protections companies seek will likely lead to a spike in drone patent litigation.

Also, because drones are a complex system, their patent landscape is equally complex. When a company wants to start commercialising drone technology, the patent landscape can be thought of as a minefield. Making the wrong move could land you in years of litigation. However, freedom to operate analyses play an important role in understanding where potential issues may be. Using these analyses can help companies navigate the figurative minefield, keep out of litigation, and shape product development.

The players and technology indicate that drones present many avenues for commercialisation from delivering pizza, helping farmers better manage their land, reshaping modern warfare, and 3D printer swarms. With many applications, entities are sure to encroach on others’ IP. It is critical for a company to understand the strength of their own IP because XiDrone Systems v 911 Security and Parrot v QFO Labs show that patents may be fallible and highly contested.

Lastly, given the sharp increase in issued patents, industry players should ensure they are also investing in patent protection. Otherwise, they will be at a severe disadvantage—without either defence protection or offensive capabilities—when addressing IP disputes.

Source: Finnegan