After years of al Qaeda commanders and operators hearing the final whistle of a drone strike seconds before meeting their end, the terror group has developed a bag of tricks for dodging death from above, according to documents recently recovered by a Western news organization.

After years of al Qaeda commanders and operators hearing the final whistle of a drone strike seconds before meeting their end, the terror group has developed a bag of tricks for dodging death from above, according to documents recently recovered by a Western news organization.

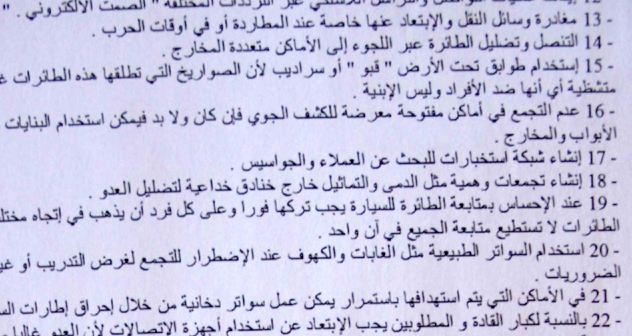

Today the Associated Press published a list of 22 anti-drone “tactics” that the news outlet said was found in a manila envelope on the floor of a building in Mali that was formerly held by al Qaeda’s North Africa affiliate, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM.

The tips, as translated by the AP, range from the obvious – “When discovering a drone is after a car, leave the car immediately…” – to the wily – “[Make] formations of fake gatherings [by] using dolls and statues to be placed outside… to mislead the enemy.”

The list also urges the militants to purchase commercial-grade Russian signals interception equipment to try and spy on the drones, hiding under tree cover, putting reflective glass on car roofs — and setting up sniper teams to shoot down low-flying drones.

The list is signed June 17, 2011 and the AP reported it has previously been posted on jihadi forums online. To download the full document, click here.

New models of drones, such as the Harfung used by the French or the MQ-9 “Reaper,” sometimes have infrared sensors that can pick up the heat signature of a car whose engine has just been shut off. However, even an infrared sensor would have trouble detecting a car left under a mat tent overnight, so that its temperature is the same as on the surrounding ground, Leighton said.

Unarmed drones are already being used by the French in Mali to collect intelligence on al-Qaida groups, and U.S. officials have said plans are underway to establish a new drone base in northwestern Africa. The U.S. recently signed a “status of forces agreement” with Niger, one of the nations bordering Mali, suggesting the drone base may be situated there and would be primarily used to gather intelligence to help the French.

The author of the tipsheet found in Timbuktu is Abdallah bin Muhammad, the nom de guerre for a senior commander of al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula, the Yemen-based branch of the terror network. The document was first published in Arabic on an extremist website on June 2, 2011, a month after bin Laden’s death, according to Mathieu Guidere, a professor at the University of Toulouse. Guidere runs a database of statements by extremist groups, including al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, and he reviewed and authenticated the document found by the AP.

The tipsheet is still little known, if at all, in English, though it has been republished at least three times in Arabic on other jihadist forums after drone strikes took out U.S.-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki in Yemen in September 2011 and al-Qaida second-in-command Abu Yahya al-Libi in Pakistan in June 2012. It was most recently issued two weeks ago on another extremist website after plans for the possible U.S. drone base in Niger began surfacing, Guidere said.

“This document supports the fact that they knew there are secret U.S. bases for drones, and were preparing themselves,” he said. “They were thinking about this issue for a long time.”

The idea of hiding under trees to avoid drones, which is tip No. 10, appears to be coming from the highest levels of the terror network. In a letter written by bin Laden and first published by the U.S. Center for Combating Terrorism, the terror mastermind instructs his followers to deliver a message to Abdelmalek Droukdel, the head of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, whose fighters have been active in Mali for at least a decade.

“I want the brothers in the Islamic Maghreb to know that planting trees helps the mujahedeen and gives them cover,” bin Laden writes in the missive. “Trees will give the mujahedeen the freedom to move around especially if the enemy sends spying aircrafts to the area.”

Hiding under trees is exactly what the al-Qaida fighters did in Mali, according to residents in Diabaly, the last town they took before the French stemmed their advance last month. Just after French warplanes incinerated rebel cars that had been left outside, the fighters began to commandeer houses with large mango trees and park their four-by-fours in the shade of their rubbery leaves.

Hamidou Sissouma, a schoolteacher, said the Islamists chose his house because of its generous trees, and rammed their trucks through his earthen wall to drive right into his courtyard. Another resident showed the gash the occupiers had made in his mango tree by parking their pickup too close to the trunk.

In Timbuktu also, fighters hid their cars under trees, and disembarked from them in a hurry when they were being chased, in accordance with tip No. 13.

Moustapha al-Housseini, an appliance repairman, was outside his shop fixing a client’s broken radio on the day the aerial bombardments began. He said he heard the sound of the planes and saw the Islamists at almost the same moment. Abou Zeid, the senior al-Qaida emir in the region, rushed to jam his car under a pair of tamarind trees outside the store.

“He and his men got out of the car and dove under the awning,” said al-Housseini. “As for what I did? Me and my employees? We also ran. As fast as we could.”

Along with the grass mats, the al-Qaida men in Mali made creative use of another natural resource to hide their cars: Mud.

Asse Ag Imahalit, a gardener at a building in Timbuktu, said he was at first puzzled to see that the fighters sleeping inside the compound sent for large bags of sugar every day. Then, he said, he observed them mixing the sugar with dirt, adding water and using the sticky mixture to “paint” their cars. Residents said the cars of the al-Qaida fighters are permanently covered in mud.

The drone tipsheet, discovered in the regional tax department occupied by Abou Zeid, shows how familiar al-Qaida has become with drone attacks, which have allowed the U.S. to take out senior leaders in the terrorist group without a messy ground battle. The preface and epilogue of the tipsheet make it clear that al-Qaida well realizes the advantages of drones: They are relatively cheap in terms of money and lives, alleviating “the pressure of American public opinion.”

Ironically, the first drone attack on an al-Qaida figure in 2002 took out the head of the branch in Yemen — the same branch that authored the document found in Mali, according to Riedel. Drones began to be used in Iraq in 2006 and in Pakistan in 2007, but it wasn’t until 2009 that they became a hallmark of the war on terror, he said.

“Since we do not want to put boots on the ground in places like Mali, they are certain to be the way of the future,” he said. “They are already the future.”

Source: ABC News