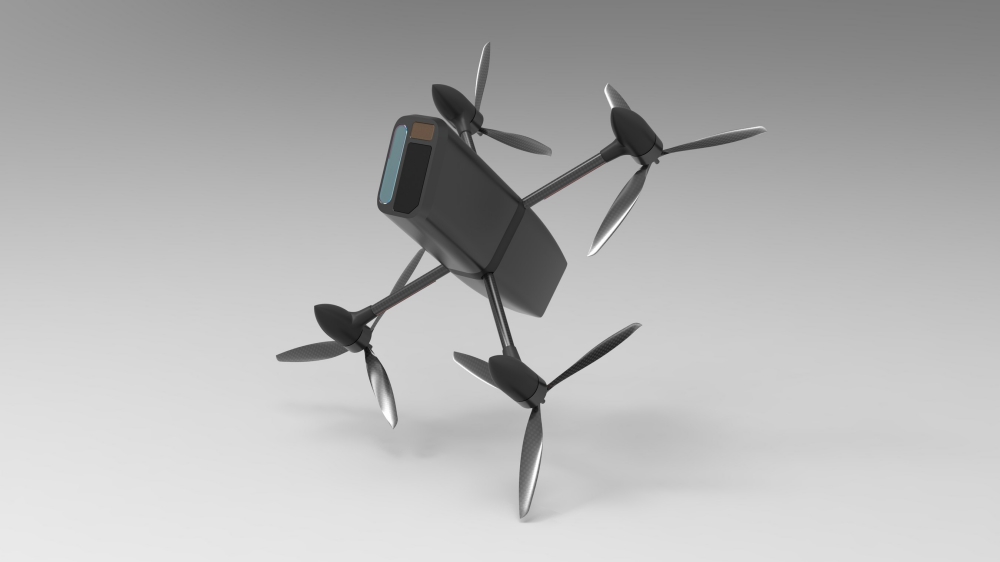

has launched the Interceptor drone as part of the Lattice AI cUAS (counter Unmanned Aerial System) solution to detect and interdict unmanned aircraft or autonomous drone systems.

This system brings proven Anduril technology to the increasingly critical counter-drone mission, providing an additional dimension of force protection for military personnel and installations or critical infrastructure.

Anduril Industries Inc., the 2-year-old startup in Irvine, Calif., began shipping Interceptors to military clients in the U.S. and the U.K. earlier this year; it’s sent dozens so far and has hundreds more in production. The company says its most recent contract is to deploy Interceptors overseas to conflict zones, though it declines to provide details. This summer it raised $120 million from Founders Fund, General Catalyst, Andreessen Horowitz (in which Bloomberg LP, which owns Bloomberg Businessweek, is an investor), and other venture capital firms. Investors valued the company at about $1 billion, four times its last funding round in 2018.

Anduril already had contracts to build surveillance systems on military bases and along the Mexican border, using towers and drones packed with cameras and other sensors. Its software then processes the field data, alerting officers and soldiers to possible disturbances. But the company wants to move beyond simply identifying threats using computers. The Interceptor, which Anduril hasn’t previously discussed publicly, is its first computer-operated weapon.

Silicon Valley has a long history of supplying the Pentagon, but the two have drifted apart over the past 50 years. Today the Department of Defense relies mostly on a few traditional suppliers such as Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman. It’s had little use for startups. Commercial tech companies haven’t been particularly enthusiastic about government work, either, and the antipathy has increased since the election of Donald Trump.

Last year a group of Google employees resigned in protest of the company’s work on a program, Project Maven, to use artificial intelligence software to analyze drone imagery. Google’s parent, Alphabet Inc., then announced it would stop working on the project, embarrassing and angering U.S. officials in the process. Workers at Amazon.com, Microsoft, Palantir, and other companies have also demanded that their employers cancel contracts with military, law enforcement, and federal agencies that are enacting Trump’s border and immigration policies.

The protesters have argued that technologists shouldn’t build products without regard for the way they’re used. In mid-September, Seth Vargo, a former employee of Chef Software Inc., a Seattle company, deleted publicly available code he’d written for its systems after finding out Chef worked with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “When I learned that my code was being used for purposes that I perceive as evil, I had to act,” he says. A week later, Chef said it would stop working with the agency.

Anduril presents itself as immune to such angst. Its founder, Palmer Luckey, is one of Silicon Valley’s most famous Trump partisans. The 27-year-old has gleefully trolled the Valley’s liberals since he left Facebook Inc. in 2017 under controversial circumstances. Founders Fund, one of Anduril’s first big investors, was started by another Trump stalwart, Peter Thiel. Trae Stephens, Anduril’s chairman, is also a Founders Fund partner and took part in Trump’s transition team. The company recently began working on Maven, the project Google dropped.

Executives at Anduril say they’re less interested in serving any particular president than in fulfilling the Pentagon’s enduring need for reliable technology. Some companies, Stephens says, have complicated things for themselves by concealing or downplaying their defense work, leaving employees who are uncomfortable with such projects to feel, justifiably, that they’ve been lied to. “They said, ‘We didn’t sign up to develop weapons,’ ” Stephens says. “That’s literally the opposite of Anduril. We will tell candidates when they walk in the door, ‘You are signing up to build weapons.’ ”

Anduril’s origins date to conversations Stephens had with his colleagues at Palantir Technologies Inc., a data-analysis company Thiel co-founded in 2004. They thought a software startup focused on high-tech military applications could outmanoeuvre traditional contractors. At first, according to Matt Grimm, who spent seven years at Palantir and is now Anduril’s chief operating officer, it wasn’t so much a plan as a bonding exercise as they sat in airport lounges or attended each other’s weddings. “It’s like that idea, ‘Hey, we should all go camping sometime!’ But it doesn’t really happen,” he says.

Palantir executives had experienced the frustrations of trying to win federal contracts. Until he left the company in 2013, Stephens worked to sell technology to the government, a job he describes as “yelling as loud as possible into the void.” The shouting did eventually pay off. Palantir sued the U.S. Army in 2016 for refusing to consider it for a large intelligence contract. It won the case and, this March, landed the contract itself, which could be worth as much as $800 million.

Such doggedness helped Palantir open the government’s door to startups, but the push for change also came from the inside. In 2015, Ashton Carter, then President Obama’s defense secretary, took a series of actions to make the government a friendlier business partner for what Pentagon bureaucrats call “nontraditionals.” After Trump won the presidency, Stephens was appointed to the Defense transition team. He later joined the Defense Innovation Board, a central part of Carter’s reform effort.

Stephens had also begun looking for defense startups in which Founders Fund could invest. Luckey, who’d sold his virtual-reality company, Oculus VR Inc., to Facebook for $2 billion in 2014, was also looking to put some of his windfall into upstart military contractors. Founders Fund had backed Oculus, and he and Stephens had become friends over time. Luckey’s career had veered off course just before the 2016 election, when the Daily Beast reported that he’d donated $10,000 to a pro-Trump group that grew out of a Reddit message board, r/The_Donald, known for incubating right-wing memes and conspiracy theories. Luckey’s money was dedicated to putting up insulting billboards about Hillary Clinton. Almost immediately, he disappeared from Facebook’s campus, and in March 2017 the company announced he was no longer an employee. (Luckey says he was fired because of his politics, a claim Facebook Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg denied before Congress in April 2018.)

With Luckey now a free agent, he and Stephens got to work on Anduril, recruiting a handful of people who’d been at Palantir or Oculus. Their plan was to follow the approach that had worked for Luckey with virtual reality: combine low-cost, widely available components with sophisticated software. Luckey figured the bar would be relatively low. Despite the lore of the U.S. military’s technical prowess, he argues, the defense industry has been stagnant for decades. “How is it there’s so many billionaires and no Iron Man?” he asks, referring to the fictional weapons-manufacturer-turned-superhero.

Luckey’s colorful public persona was bound to influence Anduril’s brand, for better or worse. At one point early on, he showed up at a Japanese anime festival dressed as a character from a video game, in a costume consisting of a bikini top and fishnet stockings. (He generally avoids cosplay in the office, but he lays on the comic book references pretty heavy no matter the situation.) Such antics haven’t been a liability, even in the buttoned-up defense business, says Joe Lonsdale, an early Anduril investor. “He’’s a more serious person than people realize.”

Anduril’s first contract, awarded in 2017, was to provide electronic surveillance technology to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) for the U.S.-Mexico border. Luckey was a strong proponent of the work—a logical way, he says, to demonstrate Anduril’s technical vision. Of course it also made Anduril instantly controversial by tying it to the Trump administration’s harsh anti-immigration rhetoric and policies.

Luckey at times has seemed to embrace this connection. Almost immediately after his departure from Facebook, he traveled to Washington to advocate for digital border security alongside Chuck Johnson, a right-wing internet provocateur. Even the company’s name called to mind the administration’s nationalist rhetoric: In the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Anduril is a sword whose elvish name means “Flame of the West.”

Critics described Anduril as either a technological manifestation of Trumpism, an amoral profiteer, or both. Luckey saw the outrage as useful. “We were telling people that border security is not going to be the last time there’s a controversy around something we’re working on,” he says. Not all Anduril employees are pleased. Grimm, who describes himself as an “Obama fanboy” and the most liberal member of the founding team, grimaces when the subject comes up. “The goal was not to set out and say, ‘We’re the border security company,’ ” he says. “It was actually quite frustrating for us through the first year and a half, because of course that was the narrative.” Anduril executives are quick to point out that many Democrats have supported electronic border surveillance as a more humane alternative to a physical border wall.

On the other hand, immigration rights advocates say companies that work with law enforcement agencies can’t ignore how those agencies treat the people being apprehended. “Assisting in that cruelty, facilitating that cruelty, making sure they have access to more people to be cruel to, it makes the whole situation worse,” says Jacinta Gonzalez, an organizer with Mijente, an advocacy group that’s put together protests against technology companies it believes are aiding in implementing the administration’s immigration policies. The American Civil Liberties Union, meanwhile, has said technologies implemented in conflict zones such as border areas or battlefields tend to seep into civilian life.

Anduril says it now takes in twice as much revenue from the military as from CBP and argues that there should be nothing controversial about providing security on bases. But the Interceptor project steers it toward another hot-button technological issue: the development and deployment of autonomous weapons.

The possible use of miniature quadcopters for spying or terrorism has concerned the U.S. military for years. The fear was underscored this year when military-grade drones were implicated in attacks in Saudi Arabia and the Strait of Hormuz, and last year during an assassination attempt in Venezuela using hobbyist drones. The Defense Department has pursued various remedies, including jamming drones’ signals and netting them like butterflies. But the idea of electronically disabling or ensnaring a drone without destroying it seemed ludicrous to Luckey. Why not just shoot it down? “All the soft kill systems are a waste of time,” he says.

He, Levin, and a handful of colleagues came up with the idea of the Interceptor while hanging around the office one weekend earlier this year. The idea was to equip small drones with computer vision software that would scan a slice of airspace that needed protecting, then automatically ram any objects deemed hostile. They built a rough prototype that could knock down its target some of the time, then shot a smartphone video of a successful attempt and passed it to their contacts at the Pentagon.

As Anduril rushed to refine its early prototypes, the military ordered a handful to try out. By summer the company was claiming a near-perfect success rate. Newer versions of the drones can reach speeds of 200 mph or more—potentially enough to knock larger projectiles from the sky. Anduril has begun building prototypes to take out larger targets, too. Luckey envisions clients who say, “We’d like to apply this to people who are not just attacking a base with a quadcopter—maybe they’re attacking it in an ultralight aircraft, or a helicopter, or a cruise missile.” Anduril plans to sell the counter-drone systems to commercial customers and has held preliminary discussions with oil and gas companies and others that have to police large, wide-open spaces.

The prospect of a 2-year-old startup building and distributing a new class of potentially lethal weapons will undoubtedly raise ethical questions, especially amid a larger backlash against overreach by tech companies. The Interceptor in its current form doesn’t target humans and requires explicit permission from a human operator before each attack, but it’s conceivable that those controls could be changed in the future. “You’ve already developed this technology, opened the so-called Pandora’s box,” argues Marta Kosmyna of the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, a group opposed to autonomous weaponry. Technologies such as the Interceptor are “very rarely used as intended,” she says.

The day after Levin’s Interceptor demonstration, employees, their families, investors, and other VIPs filtered in for an office-warming party at Anduril’s new headquarters. Luckey sat with his wife, Nicole, in a booth in the cafeteria. The couple had gotten married a few weeks earlier, and the Anduril event felt almost like a second reception. Sun filled the room, and Dave Brubeck’s Take Five played on the speakers. The crowd sipped cocktails with ice cubes that had Anduril’s logo frozen into them.

Luckey had spent the afternoon across town at a political fundraiser with Donald Trump Jr. Anduril’s founder has donated about $1.3 million to GOP-connected groups since 2017, according to Federal Election Commission disclosures, making him an important young donor in Republican circles. One of the first people to approach the cafeteria booth was Hal Lambert, an early Anduril investor and fellow GOP fundraiser, followed by a young man wearing a MAGA hat.

Guests wandered through the cavernous space under a huge American flag, checking out Anduril’s milling machines, 3D printers, and green-screen studio. The walls of every conference room were covered in complicated-looking equations. Grimm confessed he’d told employees to scrawl mathematical things to impress people without advanced degrees.

Later, Stephens and Luckey gave speeches mocking Silicon Valley’s caution about military contracts. “I’m so happy to come back down here to a place full of wonderful people who are also sane and support national security,” Luckey said, to loud applause. Stephens thanked employees for choosing Anduril over the big software companies, even though it had meant sacrificing dream careers in digital advertising optimization.

Not on hand for the event was Thiel, who’d told Stephens in a one-word text message that he wouldn’t make it. Thiel declined an interview request for this story; a Founders Fund spokeswoman, Erin Gleason, says he has “no involvement in the company,” despite his firm’s ownership stake.

Anduril’s founders present themselves as an alternative to a defense industry gone soft after decades of fat contracts. But it’s hard not to notice how deftly the company has insinuated itself into Washington circles in its short history, with prominent allies in both chambers of Congress. Tom Cotton, a Republican senator from Arkansas, says he sees the emergence of defense startups as an encouraging development. “It would be healthier if we had more defense companies to compete on Pentagon contracts,” he says.

Cotton was one of a half-dozen members of Congress who an Anduril spokesman suggested would vouch for it for this story. Another was Will Hurd, a Republican congressman who represents a Texas district along the border with Mexico. Before an interview could be arranged, though, Hurd announced his retirement, saying he was leaving the House of Representatives “to help our country in a different way.” Rumours emerged that he’d be joining Anduril. It isn’t clear how seriously anyone took the possibility, but Luckey was deluged with questions about it. “It was nice that everyone thought of us,” he says, clarifying that, though he’s talked to Hurd since the announcement, he doesn’t expect to hire him. But, Luckey adds, “I’m glad they weren’t thinking, Oh, Will Hurd is going to work for Lockheed Martin.”

Photos: MAGGIE SHANNON FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

Sources: Press Release, Bloomberg Business Week