The early 1930s saw the most extravagant aircraft with unique shapes and sizes as part of a widely experimental phase in the aviation industry. And still, the Stipa-Caproni stood apart.

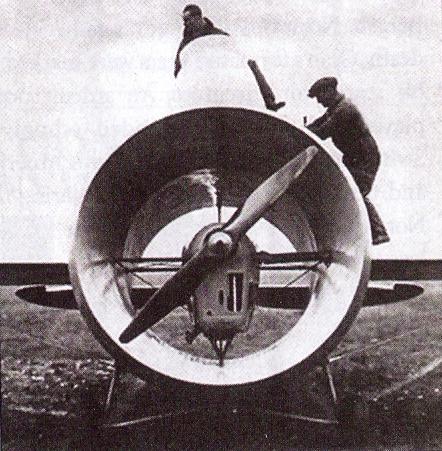

The inventive airframe designed by Italian aeronautical engineer Luigi Stipa and manufactured by the Caproni Company was in many ways like a cartoon aircraft. But it was functional! The so-called flying barrel consisted of a mere tube for a fuselage and an engine and propeller that washed the airflow through the cylinder’s length, creating thrust.

Some experts consider the Stipa-Caproni the ugliest aircraft ever built, while others still call it an aerodynamic aberration. Still, there is reason to suggest that the bizarre concoction was the direct predecessor of the modern turbofan engine…

The Stipa-Caproni, also known as the Caproni Stipa, was an experimental Italian aircraft designed in 1932 by Luigi Stipa (1900–1992) and built by Caproni. It featured a hollow, barrel-shaped fuselage with the engine and propeller completely enclosed by the fuselage—in essence, the whole fuselage was a single ducted fan. Although the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force) was not interested in pursuing development of the Stipa-Caproni, its design influenced the development of jet propulsion.

Stipa’s basic idea, which he called the “intubed propeller”, was to mount the engine and propeller inside a fuselage that itself formed a tapered duct, or venturi tube, and compressed the propeller’s airflow and the engine exhaust before it exited the duct at the trailing edge of the aircraft, essentially applying Bernoulli’s principle of fluid movements to make the aircraft’s propeller more efficient.

This is a similar principle as is used in turbofan engines but used a piston engine to drive the compressor/propeller rather than a gas turbine. Stipa later became convinced that German rocket and jet technology (especially the V-1 flying bomb) was using his patented invention without giving proper credit, although his ducted fan design had little mechanically in common with turbojet engines and nothing at all with the pulsejet used on the V-1.

Stipa spent years studying the idea mathematically while working in the Engineering Division of the Italian Ministry of Air Force, eventually determining that the venturi tube’s inner surface needed to be shaped like an airfoil in order to achieve the greatest efficiency. He also determined the optimum shape of the propeller, the most efficient distance between the leading edge of the tube and the propeller, and the best rate of revolution of the propeller.

Finally, he petitioned the Italian Fascist government to produce a prototype aircraft. The government, seeking to showcase Italian technological achievement — particularly in aviation — contracted the Caproni company to construct the aircraft in 1932.

The resultant aircraft was a mid-wing monoplane of mostly wooden construction dubbed the Stipa-Caproni or Caproni Stipa. The fuselage was a barrel-like tube, short and fat, open at both ends to form the tapered duct, with twin open cockpits in tandem mounted in a hump on top of it. The wings were elliptical and passed through the duct and the engine nacelle inside it. The duct itself had a profile similar to that of the airfoils, and a fairly small rudder and elevators were mounted on the trailing edge of the duct, allowing the ducted propeller wash to flow directly over them as it exited the fuselage to improve handling.

The propeller was mounted inside the fuselage tube, flush with the leading edge of the fuselage, and the 120-horsepower (89 kW) de Havilland Gipsy III engine that powered it was mounted within the duct behind it at the midpoint of the fuselage. The aircraft had low, fixed, spatted main landing gear and a tailwheel. It was painted in a blue-and-cream scheme of the type used on racing aircraft of the day, and its rudder bore the colours of the Italian flag.

Sources: YouTube; Wikipedia