Since Nov. 2021, researchers at Michigan State University have been working to develop a computer vision system capable of identifying individuals from 1,000 meters away. The technology, called FarSight, is the culmination of 18 months of research in cooperation with the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity, or IARPA, a federal organization that works to develop solutions for technological problems faced by U.S. intelligence agencies.

BRIAR Program Manager Lars Ericson said the impetus for the program’s creation was that some sensors used by the intelligence community were often not well-suited for performing facial recognition. Ericson pointed out that additional challenges, such as low resolution and severe viewing angles, necessitated the development of new surveillance technology.

“One can view (BRIAR) as expanding the range of imagery and the range of sensor platforms that we can perform reliable, dependable, accurate biometric activities on,” Ericson said. “That necessitates researching new types of fundamental technologies in these computer vision and machine learning based systems.”

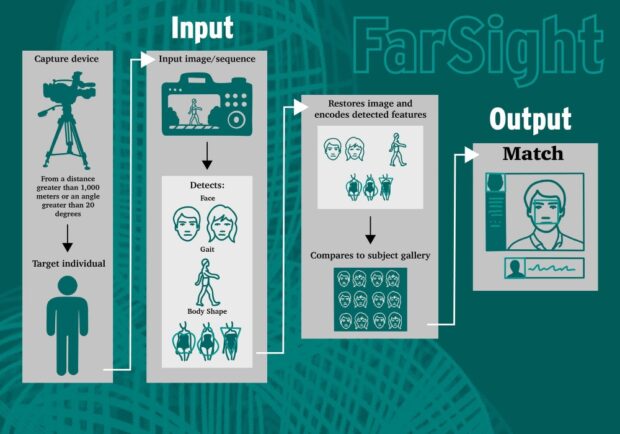

In order to successfully identify individuals from long distances, as would be necessary from a surveillance drone, for example, FarSight uses a person’s face, gait and body shape for biometric identification. This whole-body approach to identification is meant to address the challenges posed by low-image quality, individual similarities and severe viewing angles.

FarSight Project Lead and MSU Research Foundation Professor Xiaoming Liu said the software also helps combat a phenomenon called atmospheric turbulence, which occurs when light is distorted over long distances due to conditions in the atmosphere such as temperature.

“Along this way of 100 meters, because of turbulence, because of air dynamics, this (light) wave might not be a straight line anymore,” Liu said. “The face could be distorted because of this turbulence.”

According to the BRIAR program’s website, the software that ultimately arises out of this research is intended to be used for counterterrorism, military force protection and border security. As a research agency, however, IARPA does not determine the exact applications of its technology and instead works to “facilitate the transition of research results” to the U.S. intelligence community.

“(Other agencies) need to make their own assessment of the suitability, both from a technology perspective and a policy and efficiency perspective,” Ericson said. “That’s not something that we weigh in on.”

University of Tampa Associate Professor Abigail Hall, who studies U.S. foreign policy and militarism, said it’s not uncommon for technologies originally meant for military purposes to ultimately be deployed domestically. She added that although domestic use of surveillance equipment, such as drones being used for agricultural purposes, is not inherently negative, law enforcement applications of surveillance technology can be difficult to regulate.

“It’s exceptionally difficult to get information from government entities of all sizes about how these types of technologies are used,” Hall said. “For people who are concerned about civil liberties then, with things like (unmanned aerial vehicles), you have concerns about Fourth Amendment types of protections and those applications.”

Hall explained that because the work of the U.S. intelligence community is secretive by nature, it can be incredibly difficult for civilians and elected officials alike to access the information needed to effectively monitor the uses of technology such as FarSight.

“I think people can and should be skeptical when presented with any kind of new piece of surveillance technology and being told that it is exclusively and will only be used for this particular type of use,” Hall said. “We don’t necessarily have constraints that will govern how these technologies are used.”

Although Liu said he is instructed by the project sponsors to not articulate potential applications of FarSight, he provided his own perspective as a scientist and researcher.

“I feel that technology itself has no good or bad, it’s how (people) use it,” Liu said. “As a scientist, I think we focus on making the technology work to enable the possibilities.”

Source: State News